The future of affordable housing in Portsmouth

Editor’s note: This is the latest in The Sound’s ongoing look at the cost of living in Portsmouth and the Seacoast.

When urban planner Jennifer Hurley talks about affordable housing, she’s quick to issue some caveats.

“Affordability is a very complex problem with lots of moving pieces, all of which are moving in different directions,” she told a crowd of a few hundred people at 3S Artspace in Portsmouth on Jan. 28. “There is no magic bullet. There are lots of small things done in many venues in many different ways.”

Hurley was here for a two-day workshop on affordable housing, hosted by PS21, a nonprofit that hosts community discussions and workshops on planning and development issues in Portsmouth and the Seacoast.

Hurley takes a hands-on approach to her workshops, and at the Jan. 28 event, participants were seated at tables in groups of five or six, with a stack of pictures at the center of each table. Between segments of her presentation, Hurley asked each table to look at the pictures, each featuring a different type of housing — high-end apartment complexes, bungalows, cottages, in-law apartments, and so on — and make notes about what they like and don’t like about the buildings. At one table, someone taps a photo and says, “This looks like downtown New England.” The group talks for a few moments and moves on to the next picture. “I don’t think this would necessarily fit in anywhere in Portsmouth,” someone else says.

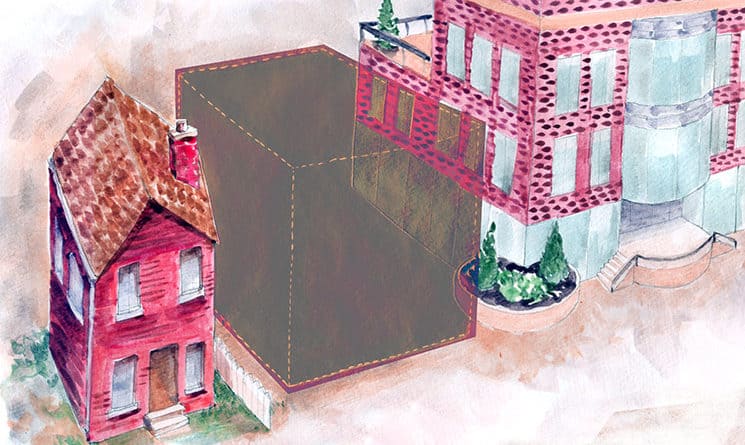

As housing prices in the city keep rising, and as more high-end condo developments spring up around downtown, city officials, advocates, and developers are wondering what sort of affordable housing will fit in Portsmouth. There are plenty of single-family homes and multi-unit complexes, Hurley said, but what Portsmouth and many other cities lack is the “missing middle” — a term coined by Daniel Parolek of Opticos Design, Inc. in 2010 about the diverse mix of small housing options that add variety to the housing stock and keep prices affordable. The future of affordable housing in Portsmouth lies in finding that missing middle. But, according to local housing experts, it’s not a simple search.

Changing definitions

The median income in Portsmouth is $68,436, according to 2014 U.S. Census data. The traditional standard of affordability, according to Hurley, is housing that costs less than 30 percent of a person’s total income. But transportation adds about another 15 percent to housing costs, Hurley said, and that changes the nature of affordability. The more a family has to spend on commuting, the less they have to spend on housing, and vice-versa. That may not be a problem in an urban area like Boston, but in Portsmouth, where public transportation is scarce, it can price renters and owners out of the city.

“There are many paradoxes that exist in the Seacoast,” said Robin Comstock, executive director of the Seacoast Workforce Housing Coalition. “Many businesses were created or moved to the Seacoast … because they are highly desirable communities. … But many employees located in Seacoast communities cannot afford to live in the community in which they’re working.”

Walkability, public transportation, and parking all influence affordability, and Portsmouth city planner Rick Taintor said that poses interesting challenges. Because Portsmouth is only about 16 square miles, “We can’t really create the robust public transit system that has the frequency needed to convince people to give up their cars,” Taintor said.

The city is changing its parking requirements, though. Taintor said developments that include workforce housing units only have to provide one parking space per unit, instead of the 1.5 spaces normally required. Small micro-housing units are required to provide half a space. Taintor said the city is also looking at shared parking as a solution in neighborhoods that have businesses and residences.

“We’re hoping to bring forward a zoning amendment sometime this spring,” he said.

Finding the middle

Transportation costs are only a small piece of the picture. One of the biggest challenges, according to Taintor, is finding interested developers — and land — for those “missing middle” projects. There are few parcels of land available, and market prices make it difficult for the city to offer developers strong incentives for affordable housing. Density bonuses — allowing developers to build additional units for every unit of affordable housing they include — are one avenue, but Taintor said working out the bonuses so the city isn’t “giving away the store” is a challenge.

The future may rest in smaller, less conventional developments, like the micro-apartments planned for the liner building at the new Deer Street parking garage. In January, state legislators approved a bill allowing communities to establish requirements for regulating accessory dwelling units (ADUs). They’re more commonly known as in-law apartments — smaller structures built on the same lot as a single-family home. ADUs currently aren’t allowed in districts zoned for single-family homes in Portsmouth.

“More outlying neighborhoods will see some of these, and these will go to the zoning board,” Taintor said. “There won’t be any affordability restrictions on them … but they’ll tend to be more affordable.”

The law goes into effect in July 2017. It could have a profound impact in Portsmouth, Taintor said, allowing ADUs wherever single-family homes are permitted.

“That’s a wide-range in Portsmouth, because a lot of areas where two-, three-, or four-family units are also allow single-family homes,” Taintor said.

Developer Chris McInnis recently filed plans to redevelop 678 Maplewood Ave. with six townhouses and a four-story apartment building with 24 apartments. Elsewhere in the city, Taintor said, developer Waterstone has plans to add 94 units of housing to the Southgate shopping plaza on Route 1 (home to Shio, Big Lots, and other businesses).

“That’s kind of a model for where potential housing growth will happen — in strip-mall shopping centers, particularly along Lafayette Road and … Woodbury Avenue,” Taintor said.

Overcoming hurdles

Doug Palardy and his husband, congressional candidate Dan Innis, have been looking for opportunities to develop micro-apartments and other projects in Portsmouth. But Palardy said finding the right project is difficult. They had plans to redevelop the former Brewster Street rooming house building, but passed on the project because the cost of the property was too high, Palardy said.

“In Portsmouth, the hardest part is finding some land,” Palardy said. “If you can develop $800,000 condos on (a parcel), most people will do that. For people who want to do (affordable housing), it’s a mission and less a numbers thing. But, at the same time, the numbers have to make it work.”

For Palardy, the numbers are easier when the development process is streamlined and the rules are clear. Going through the city’s land use boards is a lengthy process, Palardy said, and if neighbors object, it can put a project in limbo for months or years.

“I think developers in this town are very scared to develop something that’s not a big money-maker — your risk is much higher,”

he said.

At the PS21 event, Hurley said another impediment to affordable housing is that simply advocating for it at city hall is a “deeply unequal” political activity. The lower your socioeconomic status, the less likely it is you’ll be able to attend meetings or engage with public officials.

Workshops and meetings on affordable housing can go a long way toward solving the problem. But, Hurley said, when those meetings are primarily attended by older white people with high incomes, the input of a vital segment of the affordable housing equation remains missing.