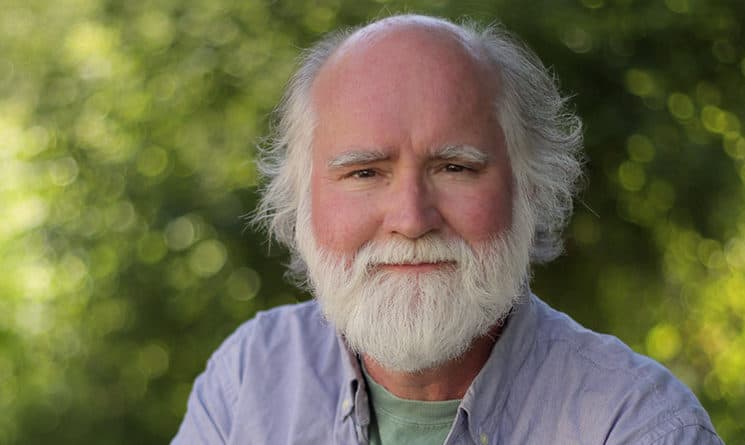

Nicholson Baker discusses writing, Seacoast-based characters, and saving newspapers

by Craig Robert Brown

Nicholson Baker made his mark on the literary scene with his debut novel, “The Mezzanine,” in 1988. Since then he has written more than a dozen books of fiction and nonfiction that cover sexuality, history, politics, literature, poetry, and everything else that grows in what he calls the “botanical gardens” of our minds.

Baker has also made the Seacoast, or at least, a slightly fictionalized version of it, a literary destination. Baker lives in South Berwick, Maine, and his favorite protagonist, Paul Chowder, the subject of his novels “The Anthologist” and “The Traveling Sprinkler,” resides in Portsmouth and stops by some familiar Seacoast locales in his travels.

Baker will read as part of the University of New Hampshire’s Writers Series on Thursday, Feb. 12 at 5 p.m. in the Memorial Union Building in Durham. The Sound recently caught up with Baker on a snowy morning to talk about writing, humor, and his advice for writers.

You were recently in India for the Jaipur Literary Festival. How was it?

It was an incredible experience. I had no idea it was so big. It was billed as the largest, free literary festival on Earth and it has to be true. It seems like everybody in this ginormous city of Jaipur goes there, but also people from around the world. There are tents and there’s music and there’s tremendous crowds of enthusiastic people. They have these interesting panels on different subjects from India and Pakistan’s relationship, or writing about war, or writing about sex, all sorts of different topics. And they treat the writers very well and put them up in wild hotels around the city. I’m still recovering.

With your first novel, “The Mezzanine,” you established what some call a plotless narrative. There’s a stream of conscious style to the writing. Why do you feel you gravitate to this style when you write?

I think of it not so much as plotless as I have brought the plot down to a more human scale. In “The Mezzanine” there is a plot, it’s just very humdrum. The hero has to ride an escalator and the escalator, in a sense, is the plot; you start at the bottom and you go up and you end up at the top. But there’s also the errand to buy shoelaces. There’s something that happened that is compelling the character to do things; it’s just that nobody’s died, no war has been declared. No big things. I think of it as human scale narratives more than plotless.

That makes sense. If you think of John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer” it’s just a guy swimming in different pools in his neighborhood, but the real narrative plot takes place in his thoughts while he swims.

And why not? We do have rich foliage, whole botanical gardens of interesting and strange things growing in our heads. We might as well slow down and pay attention to things and not rush forward. There’s no reason to rush. Not that (intense) novels and movies aren’t interesting. I do like them; it’s just not something I can do.

In “The Anthologist,” the protagonist Paul Chowder says: “It’s hard to hold it all in your head. All the different possible ways that you can enjoy life. Or not enjoy life. And all the things that are going on.” Is this how you feel about your own mind, and maybe why your writing is stream of consciousness?

The Anthologist” is fairly autobiographical, so many of the thoughts in there are my own thoughts. And it is hard. We’ve got so many interesting things to think about, it’s kind of mind scrambling to know what to turn to next and how much of your attention to give something. The last two Paul Chowder novels are trying to do a better job to capture (thoughts). One moment you’re thinking about the history of poetry, the next moment you’re thinking about music, or some grand idea, and the next moment a piece of your egg salad sandwich might fall in the silverware drawer amidst the forks and you think, “Oh damn.” Maybe a little political indignation sneaks in there. What are you going to do with that? Real life is a multi-colored wheel that is always turning all the time with different objects of attention, and we’re always having to decide where the wheel is going to stop at any one second. It seems truer to write a novel that embraces all of that confusion.

What is it about Paul that makes him an interesting character that you wanted to keep coming back to in your writing?

I liked Paul Chowder. I liked his set up here; he lives in Portsmouth. I’ve lived in South Berwick, Maine, for 15 years now and I have more of a connection to this place than some of the earlier places I’ve lived. He’s trying to figure it all out, which is what we’re all trying to do; bumble through life and figure it out. He has some setbacks, things go wrong for him (in the second book his whole barn floor collapses). Bad things happen, but not bad things that are paralyzing or immobilizing. He has plenty of room to think about the outside world: history and politics and poetic meter. I think it’s nice when a novel does one of the old-fashion duties of the novel, which is to show how something works. To give the reader a tip or a trick about living. It actually helps. I’m always grateful when I’m learning something about life. I like to put those in my books if I can.

In your novels “Vox,” “The Fermata,” and more recently, “House of Holes,” you’re not afraid to tackle the topic of sex and sexual desire amongst men and women. But in doing so you’ve received criticism as being pornographic. Why do you think those novels received that type of criticism?

Well it’s interesting that you talk about the criticism. I haven’t noticed it so much. I guess it depends. I lived through a whole wave, many sexual revolutions, but I wrote “Vox,” it came out in 1992, and the whole book was a giant sex scene. That was unusual, with two people talking on the phone seducing each other. And the phrase that begins the book, “what are you wearing,” I hear it in movies whenever two people are talking on the phone. [Laughs] I’m kind of thrilled by that. It’s going to be on my tombstone: Nicholson Baker 1957 to whenever, “what are you wearing?” But then I wrote another book (“The Fermata,” 1994) that’s a fantasy about stopping time and really quite filthy, and that one did get criticized. The first one did really quite well. I remember the Cosmopolitan review was one of the most thrilling reviews I’d ever gotten; I think it said, “too wrung out to go on [laughing].” “The Fermata” was a little darker and the character wasn’t asking permission and that really … ticked some people off in England. The worst reviews I’ve ever gotten were in England. Skip ahead to when “House of Holes’ came out a couple years ago (2011); we’re now kind of slumping around in marshes full of sexual imagery, so it’s a totally different world. Now I don’t think I’m being criticized for being sexual in the same way. I think now they think, “Oh my gosh he’s still at it? He’s still going to write about that?” I think it’s more like that than I’m somehow being subversive, because it isn’t subversive to write about sex anymore. It’s certainly familiar and common, and the whole world of what is possible in books and on screen has changed. And I think that’s probably a good thing. What I wanted to do (in “House of Holes”) was take it over the top and try to be really raunchy but funny at the same time. Because sex is funny and absurd. I was curious to see what happened. I thought, “Where can I go with it?”