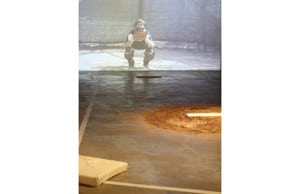

It’s the bottom of the ninth. Two outs. Three balls, two strikes. But the pitcher’s mound and the bleachers are empty.

Tyler Lafreniere, a Brooklyn-based artist who was raised in Maine, has transformed Buoy Gallery in Kittery into an abstracted baseball field, a perfect place to consider contemporary masculine identity.

“Baseball occupies a heroic space as the all-American male sport,” Lafreniere says.

He looks at manliness through iconic cultural imagery, recreating objects and scenes as both an homage to the originals and as a way to encourage critical reevaluation. In this exhibition, titled “Take Me Out,” he takes away the perceived value of baseballs in protective cases by omitting the signatures, and he gives more value to foam fingers by meticulously painting them in limited editions. He leaves the infield empty so the focus shifts from the familiar pastime to a collection of objects that at once feels both sacred and absurd.

The idea of masculinity in crisis is not new, but is increasingly relevant as we move further away from traditional gender roles and expectations. The formerly accepted idea of men in power now seems limited to the locker room or playing field, or even a man cave. Lafreniere argues that it’s not so much a crisis as an opportunity, and he recreates men’s spaces in a way that let’s us consider what we win and lose when on a level playing field.

The professional baseball field continues to be exclusively male, and Lafreniere says sports remain an integral part of how we define masculinity, although the definition is expanding. The Sound recently caught up with him to find out more about his ongoing, creative exploration of what it means to be male.

What prompted your study of masculinity?

I’ve been specifically addressing masculinity in my work for some years now. I’ve always been interested in finding ways to examine personal relationships in reference to my own masculinity within a larger societal context that is also relatable to a wider audience.

I feel that our culture’s relationship to masculinity is particularly complicated and confused at the moment, which makes it all the more interesting to study. I cannot count the number of times, as of late, that I’ve seen “crisis of masculinity” used in contexts ranging from gender roles in the workplace to the fashion trend of beards and flannel, or “lumbersexual.” I don’t see these complications as a crisis. I see them as an opportunity to expand the readings of traditional cultural ideas and spaces.

Is there a certain type of male bonding that’s essential to being male?

I’d like to think our definition of being male is expanding to a point where there aren’t essential qualities to that definition. However, there have been, and continue to be, numerous bonding spaces that are traditionally male. Sports, specifically, serve as a commonplace for male bonding.

On the surface, there are many established ideas about how sport is related to masculinity, such as “guys like sports” and “real men know how to throw a ball,” etc. I am interested in scrutinizing these tropes in the analytical context of fine art to specifically raise some of these complications.

Why leave the “playing field” absent and the baseballs unsigned?

I was highlighting some tensions of this space and these objects that are usually ignored. For example, going to a park and seeing an empty playing field raises very different emotions than encountering the same space situated inside of a gallery. While the former might feel nostalgic, the latter raises questions that move the familiar objects (baseballs, scoreboards, the diamond itself) into a position where we can look at them differently.

Buoy is at 2 Government St., Kittery, Maine. Gallery hours are 4 to 10 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday. The show ends June 26.