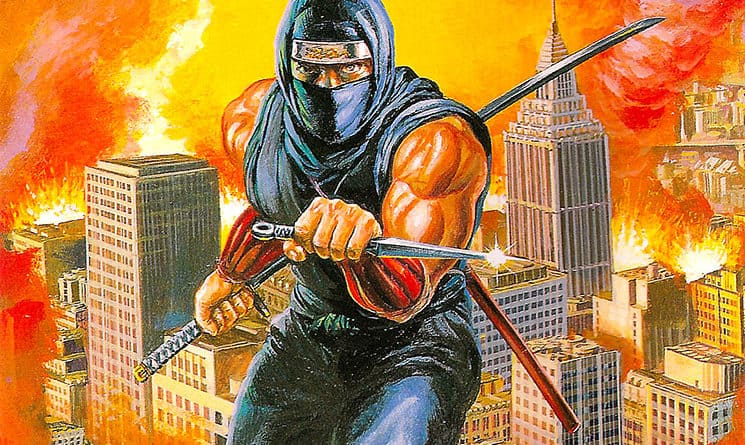

“Ninja Gaiden” (Tecmo, 1989)

By the start of 1989, Japanese video game company Tecmo was known for Nintendo games stupid (“Mighty Bomb Jack”), difficult (“Solomon’s Key”), and stupidly difficult (“Rygar”). They shed their negative digital baggage with the release of “Ninja Gaiden.” No other title would ever be able to match the quality of the storyline, the intricacy of the gameplay, or the soul-crushing difficulty of the title that introduced the world to Ryu Hayabusa.

“Ninja Gaiden” (pronounced “GUY-den”) raised the bar from its first minutes with a cinematic opening that still impresses 27 years later. One ninja clad in white, one red, menacingly stare at each other across a moonlit field. Quick close-ups, first of their exposed eyes, then fleet feet as they charge, jumping impossibly high, perfectly framed by the moon and accompanied by a fast, exciting score. Their katanas clang and the screen flashes. The red ninja collapses dead. Mournful music plays as we cut to Ryu Hayabusa, a ninja in blue reading a letter his father — the deceased red ninja — left behind. Along with the letter, Ryu is given the family’s Dragon Sword and instructions to travel to America to meet with an archeologist. Ryu promises, “I will get my revenge!” Mystery. Tragedy. Archeology. This was a step up from the typical “save the princess” eight-bit plot.

The game doesn’t abandon its theatricality after the opening scenes. It embraces it — there are Amazon temples, evil demons, and CIA machinations to contend with. The first level finds Ryu thrown into a gritty, broken-down metropolis with only his Dragon Sword and throwing stars to help beat back big bosses Barbarian, Bomberhead, Basaquer, and Bloody Malth.

Through six acts, the plot keeps twisting. Consider the “love story” at the heart of what would become the “Gaiden” trilogy: Ryu and Irene. Ryu’s first words to Irene upon finding her are, “Who’s there? Just a girl. Get out of here!” Irene responds, of course, by shooting him. The shocks keep coming as the CIA’s true loyalties are questioned, hostages are taken, catacomb trapdoors are revealed, and new light is shed on the battle shown at the start of the game.

All games increase in difficulty as they progress. But “Gaiden” broke down even the most persistent players with its punishing onslaught of enemies and demanding jumps and patterns that required repeated play to memorize. “Repeat” being the key word. In Act 3-2, Ryu’s ascent up a snowy mountain is filled with nigh-impossible jumps, heat-seeking giant eagles, sword throwing zombies, and endless bazookas. Death equals instant level restart. But, unlike games like “Battletoads” or “Rygar,” persistence equals progress.

“Ninja Gaiden” never compromised its story or its difficulty level. It made better (if not more psychologically damaged) players out of a whole generation of gamers and begs to be revisited almost three decades later.

Hidden Jewel or Total Junk:

Not-So-Hidden Jewel