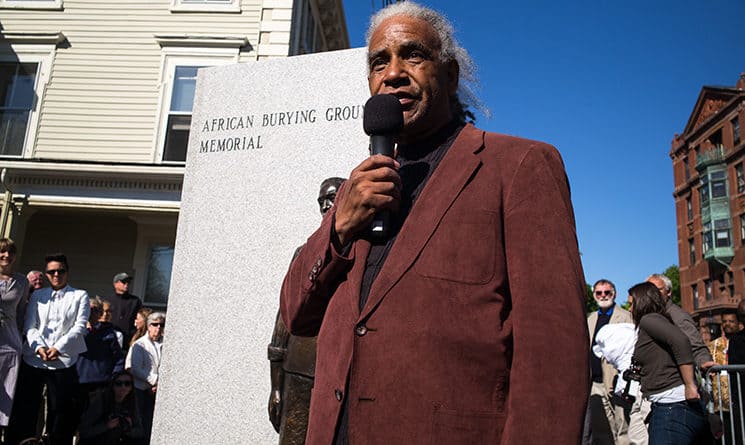

The opening of Portsmouth’s African Burying Ground memorial on May 23 was the culmination of a decade-long community project. Savannah, Ga.-based artist Jerome Meadows joined the project in 2008 and designed the memorial park located on Chestnut Street. Before the memorial opened, The Sound sat down with Meadows to talk about his hopes for the project, race, and the psychology of public art.

You grew up in the ’60s, and I’m wondering whether the events of the last two years — Trayvon Martin, Ferguson, Baltimore — have changed or enhanced this project for you?

In all truthfulness, I began to feel somewhat — I don’t want to say jaded — but disappointed that the hard work of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s seemed to have not fulfilled itself. I live in a neighborhood that’s pretty much the ghetto, and I look at folks who are struggling with respect to economics and politics and it just seems like there’s such a disparity between where a lot of the society is now compared to where it was headed back in those days, and so it leaves me wondering why that is. And then these movements are coming about, and that’s encouraging because it seems to be harkening back to those days. But I guess I feel concerned about how they can prove to be beneficial, and looking at it this way is my sense that it’s the same political-economic-sociological dynamics, and we need to bring something new into the discussion. And what I don’t see in the discussion a lot is art and culture, and so it’s quite encouraging for me to be working on this project. Art is being utilized in a way of reparations, if you will, sociological reparations, by restoring dignity, and so it just reaffirms for me that what needs to be brought into the discussion nationally is culture, art, something that would help to break the gridlock, cut through the adversarial nature of these opposing forces. So I would hope that with this project here, by being a monumental assertion of culture within that racial context, we’d get the kind of play that would put it out there for other communities to consider.

A mother and child take in the new African Burying Ground Memorial sculpture.

So do you hope your work here starts a certain dialogue?

It certainly could, but again, a dialogue that’s not couched in “me versus you.” I think it’s just interesting that the subjects of the piece are where it all started — African people being brought into America. So we’re really taking about them, and perhaps in talking about them we can come together collectively with a common cause rather than talking at each other.

Speaking at 3S Artspace (on May 20), you said people are conditioned to order things, things like shapes and colors.

Yeah, the brain is like, “Let’s categorize all of this, put this in some kind of order.”

How do you want or expect people to order or categorize this work?

There’s a lot there. I tried to take into account (that) public art, by its nature, is often experienced by people who were not looking for it; they’re not thinking about art, they may even be thinking that art is a waste of time. So I like to include elements in there that, even for those individuals, there’s something they can look at and draw them into it. There’s such a variety of visual elements, but of course, the whole thing is about these enslaved people who were buried and disrespected and disregarded for so long, so that would be a common objective in terms of what should be on people’s minds.

Pallbearers carry one of the caskets to the crypt during the reburial ceremony.

Tell me a little bit more about the implicit or subliminal effect of art. What is it, what does it lend itself to, and how might it play out with this project?

I think part of it has to do with this idea that the mind is looking to put things together in such a way that they become meaningful, that they become discernible. In designing this space, you’re walking through an environment that is rather specific and precise and it’s designed to take you out of the normalcy, or the mundaneness, of streets and concrete and asphalt and rectilinear environments so the minute you step into the site, psychologically, whether you are aware of it or not, you are in a different kind of environment in terms of how you move through it and that is designed to be more humanistic. I would hope that once a person comes off the site they’re thinking, or they have a heightened awareness of, what other environments are like. In other words, being taken out of the rat race and being put in a space that’s engaging, so when you go back in the rat race, maybe you feel a little less willing to settle for that.

When I think of the rat race, I think of competition, things that don’t foster empathy and tolerance. Where do those concepts fit into this project?

Those entry figures are street-level, they’re life-size, and I’ve designed them in such a way that I’m hoping will create a sense of connection with these people — so you’re walking down the street and all of a sudden there’s this person standing there. Are you compelled to interact with him or her? And then realizing what that person represents, to get into their story. I’m also intrigued by what happens when strangers end up at the site at the same time. To what extent might they find — instead of passing each other as we often do — a compulsion to interact with each other on the basis of slowing down and being about the issues and the concepts. That can be racial, but it can also just be what it’s like to be human.

The Blind Boys of Alabama perform at a community celebration at The Music Hall.

In the process of creating this, did you experience anything new?

I did, especially with the life-size figures, the male in particular, because he represents the first enslaved person here in Portsmouth. I’m thinking, “Yeah, I know about slavery, I know how horrible that was.” But, when it came to dealing with him as a person and his face, I found myself really at a loss as to how deep I need to go into what that mental experience had to have been. Because his face has to express something, and quite frankly, it took a while to really go into that space and sort through the intense emotions. I had to balance that against what I want for a connection between the average person walking down the street not looking for art, not thinking about art, and suddenly they’re confronted with this figure and they’re compelled to engage rather than turn away.

What do you draw on in order to capture those emotions?

Really, what it came down to, what made it so different, after the imagination, the history, was simply humanity, being a human being. This may sound strange after all these years, but I never approached or thought of the institution of slavery to that degree of personal involvement with it. Yes, the imagination would make me think, “Wow, the middle passage must have been horrific, the sense of indignity and confusion.” But, because of the nature of these figures, I really found myself going into a level of humanistic depth that I had not before, and it took a while to go in there, sense what that was, and come out with something that was telling of that, but at the same time, engaging with a public who you have no control over