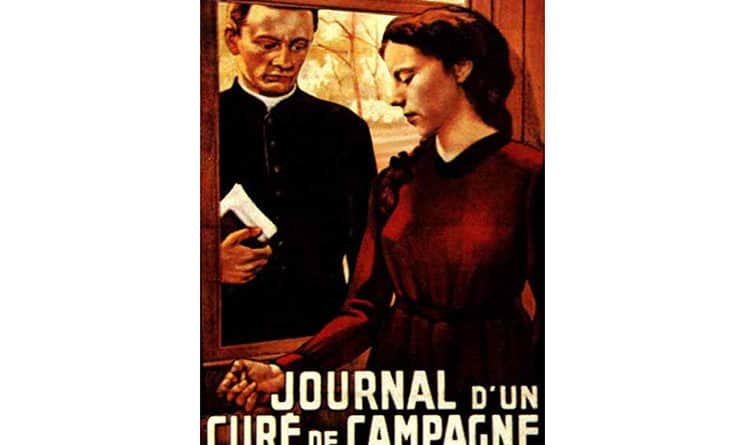

“Diary of a Country Priest”

Brandon Films, 1951

Starring: Claude Laydu, Andre Guibert, Marie-Monique Arkell

Director: Robert Bresson

The plot: An awkward young priest (Laydu) arrives at his new parish in a small country village, where he receives a chilly reception. He is mocked by the girls in the catechism class he teaches. His colleagues have nothing but contempt for his ascetic lifestyle and sparse diet. Concerned about the daughter of the local countess (Arkell), the priest visits and apparently reaffirms her commitment to God after a period of doubt. The countess dies, and her daughter spreads rumors that the priest hastened her death. An older priest (Guibert) talks to the younger one about his poor diet (bread soaked in red wine) and lack of prayer, but the younger man seems unable to change. A doctor diagnoses him with stomach cancer. The priest goes for refuge to a former colleague, who has left the priesthood and now works as an apothecary, living in sin with a woman.

Why it’s good: Based upon the excellent pastoral novel by Georges Bernanos, this film saw Bresson adopt the approach that would become the hallmark of his style — non-professional actors, an abandonment of psychological subtext or motivation, and markedly static camera work and editing. Laydu’s debut performance as the tormented priest has been described as among the greatest in the history of film. “Diary” was a triumph with audiences and critics alike (winning the grand prize at Venice) and has continued to be admired by established directors such as Martin Scorsese, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Jim Jarmusch and new viewers alike.

The legacy: An ultra-minimalist, Bresson’s influence on French cinema was described thusly by Jean-Luc Godard: “Bresson is French cinema as Dostoevsky is the Russian novel and Mozart is German music.” Screenwriter and director Paul Schrader was so enraptured by Bresson’s singular work that in 1972 he wrote a brilliant, if bravely esoteric book, “Transcendental Style in Film,” deconstructing the work of Dreyer, Ozu, and, particularly, Bresson. It’s amazing Bresson found an audience and backers: films like “Pickpocket,” “Mouchette,” and his quintessential achievement, “Au Hasard, Balthazar,” defy much of the conventional wisdom of cinema storytelling: a stationary camera, unadorned production values and performances devoid of variety or psychological nuance. Utilizing a meticulous and strict precision of style with absolutely no regard for commercial potential, Bresson saw cinema as an opportunity to break from the artifice of theater. He routinely put his “models” (his term for actors) through multiple takes until all semblance of artificiality was stripped away. Andre Bazin wrote that Bresson “stirs the emotions, rather than the intelligence.” Although ranked with Jean Renoir as among the most important French filmmakers, and invoked as an elder of the French New Wave, Bresson’s deep interest in Catholicism (as well as his flirtation with Jansenist heresy) was often a stumbling block for admirers. The Criterion Collection offers a beautiful edition of this sublime film, as well as collections of Bresson’s other features.