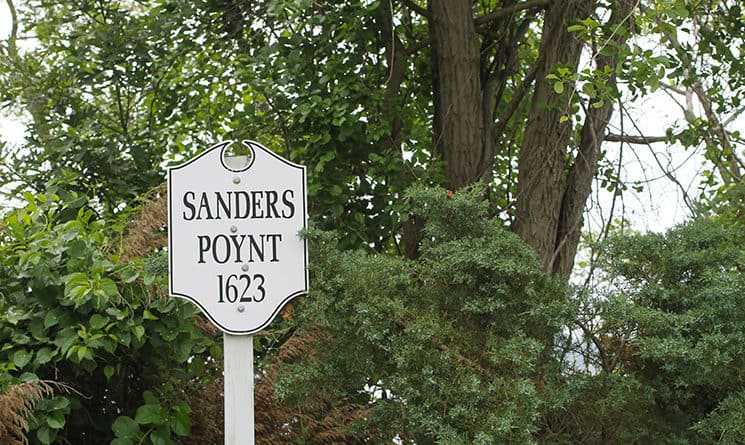

Robert Jesurum has used Sanders Poynt to get to Rye Beach for more than two decades. It’s a tradition that, according to his research, goes back hundreds of years. But the tradition ended in 2012, when the Wentworth by the Sea Country Club erected a fence and placed juniper bushes and boulders in front of the parking area on Route 1B that granted access to Sanders Poynt and the beach.

Since then, Jesurum, and the town of Rye, have been engaged in a legal battle with the Wentworth’s owner, William Binnie, to restore public access to Sanders Poynt. A Nov. 26 ruling by Rockingham County Superior Court judge Marguerite Wageling found that the public can use Sanders Poynt to get to the beach. The ruling did not specify how much access the public has to Sanders Poynt, which is located on the Wentworth’s golf course, and which Binnie owns.

A trial scheduled for June 25-26 at Rockingham County Court House will determine how the public can access the land. And, while Jesurum is optimistic about the outcome, he admits that the trial may not be the end of the story.

“This is the third summer we’re without that land, and I don’t know how much longer this will go on,” he says.

Jesurum has lived near Sanders Poynt for 24 years. When the country club blocked off the parking area, Jesurum went to town officials and protested what he calls a “land grab.” But the town initially didn’t challenge the country club.

“I didn’t like seeing what happened, and I tried to get Rye to reverse it,” Jesurum says. “It was one step after another, and then I was caught up in this.”

“It’s a beautiful place to stop and park and look at the moonrise or watch the harbor. To let that just disappear is a travesty.” — Robert Jesurum

Since then, he’s mounted a one-man fight to keep Sanders Poynt open to the public. In the process, he’s wracked up thousands of dollars in legal fees. The Coastal Conservation Association of New Hampshire set up a Sanders Poynt legal defense fund earlier this year, and contributions to the fund have helped pay for a small percentage of the costs. The nonprofit group Friends of Sanders Poynt has also helped with the case, according to Jesurum. He’s asked the state attorney general’s office to investigate the case, but the AG’s office declined, Jesurum says.

“It’s not cheap to do this, and my personal feeling is that it’s disgraceful that the only way this will be stopped is if a private citizen did it. It’s not the way a state or town should be run,” he says.

Attorney Benjamin T. King represents Binnie and the country club. He says the country club has “never been opposed to granting the public access to the public beach area.”

“The dispute arose due to infringements on the Wentworth’s private property rights that led the Wentworth to become concerned about damage to its bucolic property and the need to protect the property from damage and injury,” King says.

Jesurum alleges that blocking public access to Sanders Poynt is less about protecting the Wentworth’s property from damage than it is about increasing private property values at the expense of public land.

“I don’t think (Binnie would) do this unless there’s money involved. There’s value in that land,” Jesurum says.

The 2014 ruling found that Jesurum and the public have a prescriptive easement on the land, meaning the public can access it even though it’s owned by someone else.

“It’s been public land forever, but it is privately owned. They’re the owners, but they’ve never really established control over it” until 2012, Jesurum says.

He hopes the trial will restore full public access to Sanders Poynt. But, even if the ruling is in Jesurum’s favor, the Wentworth can appeal the 2014 ruling to the state Supreme Court, King says.

“We certainly plan to appeal the finding that any prescriptive easement exists,” he says.

Whatever the outcome, Jesurum believes this is a “landmark case” that’s “protecting public land against private encroachment.”

“It’s a beautiful place to stop and park and look at the moonrise or watch the harbor,” he says. “To let that just disappear is a travesty. New Hampshire has 10 or 15 miles of coastline, and that’s not very much … that’s why it’s important.”