Jim Splaine remembers the first time he saw his father cry. It was July 11, 1966, a Monday night, and Splaine and his family were on their way home from a Portsmouth city council meeting. That night, the council had voted 7-2 in favor of a plan to raze the North End, the densely packed urban neighborhood near the railroad tracks that cut through the city, to make way for new industrial and commercial development.

Splaine’s family, like many of the hundreds of families who lived in the North End, had deep roots there. The family lived at the corner of Deer and Bridge streets; Splaine’s grandfather had bought the old three-story house in the 1930s. The top two floors were apartments; the ground floor was a popular neighborhood bar where Splaine’s grandfather claimed to serve “the coldest beer in town.” Splaine learned to ride a bike in the parking lot where Gary’s Beverages now stands — which, in a few years, will be torn down to make way for the city’s new parking garage.

“That was our playground and our neighborhood,” says Splaine, now Portsmouth’s assistant mayor.

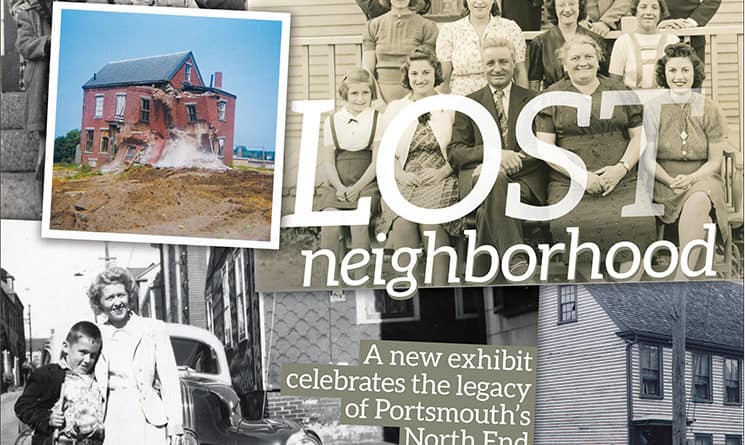

It’s hard to imagine today what the North End looked like. The urban renewal plan councilors approved in 1966 left few traces of the neighborhood. Houses and buildings that had stood for centuries vanished and were replaced with boxy buildings and massive parking lots.

James Smith, photographic collections manager at the Portsmouth Athenaeum, hopes a new exhibit opening Feb. 12 will help modern audiences see what it was like to live in the North End. “The North End: A Lost Portsmouth Neighborhood” is a multimedia exhibit of photos, paintings, poems, furniture, and other artifacts tracing the legacy of a neighborhood that disappeared — and is now making a comeback.

Portsmouth’s melting pot

Before the North End was the North End, it was an orchard, according to Smith. The Cutts family, one of the first to settle in Portsmouth, owned the land. Over time, the 26 acres became a “colonial neighborhood with narrow streets and densely clustered housing,” Smith says. By the mid-19th century, the railroad, operated by the Boston and Maine Railroad Company, transformed the North End into a bustling gateway.

“If you traveled by rail, which in those earlier times everyone did, you’d have to go through the North End to get downtown,” Smith says.

The railroad meant diversity. Immigrants from Italy, Greece, Poland, China, and Sweden headed north from Boston and made their homes in the North End. Those immigrants mixed with African-Americans and old-time New Englanders to make the area a “true melting pot,” Smith says.

The Donini Family of Portsmouth’s North End, circa 1939. photo courtesy of Marie and Bruno Genestreti

That’s what Splaine remembers most about the neighborhood. Families of different cultures, races, and religions lived side by side. Young children went to the Farragut School, which was located near where the Sheraton Harborside Hotel now stands. Take a walk through the neighborhood and you’d smell Chinese food, traditional Greek dishes, and every other kind of food imaginable.

“I don’t think Portsmouth would be what it is today without that diversity,” Splaine says. “I thought that was the way the world was.”

Neighborhood lost

Spurred by federal grants and a desire to get drivers off highways and back into downtowns, urban renewal projects spread across the country in the 1950s and 1960s.

“All throughout New Hampshire, in towns like Somersworth and Dover, or in Newburyport, Mass., there was this idea that to get people downtown, you had to clear the downtown,” Smith says.

Officials thought the North End was too congested and full of what looked like derelict buildings. From their point of view, according to Smith, urban renewal was cleaning up the area and creating a better Portsmouth.

But families who’d lived in the neighborhood for generations lost their homes and the city they knew. After that 1966 meeting, Splaine says, families in the North End began selling their homes to the Portsmouth Housing Authority, which was in charge of the project, and moving elsewhere. Over the next few years, the North End disappeared building by building.

Splaine’s parents bought a new home on Willard Avenue. His family knew when their house was slated for demolition and made sure to steer clear of downtown that day. “It was very sad,” he says.

Rethinking history

Smith began working at the Athenaeum in 2010. A discussion with a colleague about the North End turned into a years-long project that eventually involved collaborations with Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth Public Library, the local chapter of the Sons of Italy, and other groups.

In 2013, Smith received a grant from Historic New England to take the Athenaeum’s collection of North End photos and “digitally repopulate” the North End. The library had its own collection of photos of North End homes just before they were torn down, and Smith’s job “was to match the families (in the Athenaeum’s photos) with the homes (in the library’s photos).”

Residents of 33-35 Deer Street in Portsmouth’s North End, circa 1935. photo courtesy of Michael Pesaresi

In the meantime, other groups began collecting oral histories from residents who grew up and lived in the neighborhood. Artifacts began pouring in, and before long, there was more than enough material for an exhibit. The display includes more than 300 photos, doors that were used in North End homes, pottery shards excavated from the site of the Sheraton before it was built in the 1980s, and more.

One corner of the exhibit is staged to look like an early 20th-century living room, with an old-fashioned couch and antique wallpaper. It’s a place for people to reflect on the neighborhood and imagine what it was like to live there.

“We want to let people know what was there, who the families were, and let them know this was a very important neighborhood in Portsmouth. While we can’t say what will be built there now, we can say what was built there then,” Smith says. “We’re hopeful we’ll get families coming in who will recognize relatives or see themselves.”

Delayed revival

The reality of urban renewal never matched the vision. Commercial developments like Vaughan Mall and Parade Mall never really took off, Smith says. An area that had evolved from an orchard to a bustling, vibrant neighborhood had been torn up at the roots. For decades after, the North End was home to industrial buildings, blocky commercial spaces, and parking lots.

“It never had the opportunity to evolve again because of urban renewal,” Smith says. “It killed the neighborhood that was existing there.”

The last decade, though, has seen a surge of development in the North End. Big projects like Portwalk Place and the long-planned HarborCorp development are bringing residences and businesses back to the North End. Last summer, city councilors approved plans for a new parking garage located at the corner of Deer and Bridge streets, and there are plans for micro-apar