It’s not apparent, at first, that the artist walked on the painting or that he encouraged people to throw things at it. The first thing you notice is not the footprints, just that the painting spans more than 40 feet wide. But, Nathan Miner wants us to slow down and look closer.

The panels of “Entanglement” fill a whole wall, as surrounding and bewildering as being inside someone else’s head. But in time, there’s a shift. And finally, a footprint.

The two new shows at the University of New Hampshire’s Museum of Art leave a big impression with mural-scale pieces and memorable statements. “Groundswell” and “Natural Wonder” are on view through April 3.

Miner’s paintings are a form of creative resistance to the fast pace of our times. They are slow to make as well as to appreciate. “Entanglement” was eight months in the making. It began on the floor of his studio with photos and prints adhered to aluminum. He drew on it, took notes on it, and let it collect dust. He spent days dipping his feet in paint and walking over it, and let viewers leave their marks by throwing coins at it. However, he took great care painting the surface layer. The intent is to engage people so that the painting exists within them as well as in front of them.

The three artists in “Groundswell” undergo lengthy, complex processes that depend on technology at some points, and then contrast it with deliberately slow, traditional and labor-intensive methods.

Sophia Ainslie’s distinctive style incorporates an X-ray, maps, and place sketches. She creates a digital collage, then projects the image onto the canvas where she paints it with bold strokes of India ink, juxtaposed by flat color and white space. The result is confusion between whether the work is handmade or printed, raising questions of perception. The imagery represents a universal connection of body and landscape. But it has personal meaning too, since the X-ray was taken of her mother.

Cristi Rinklin’s source material comes from sampling details of paintings, wallpapers, search engines, and photographs. She also makes a digital collage, but then slowly recreates it by hand, refining it layer by layer.

Rinklin is interested in the way a constructed reality, whether historical or virtual, can reflect subconscious desires and fears. Though she focuses on landscapes, they become uninhabited fragments floating in ambiguous space. The combination of realism and abstraction, as though viewed through a kaleidoscope, is disorientating and suggestive of an uncertain future. There is, however, some comfort in the idea of life outside of and beyond our existence.

In the gallery space downstairs, four more regional artists are featured in “Natural Wonder.” While “Groundswell” focuses on specific locations as departure points, this exhibition looks generally at the natural world.

Shelley Reed’s mural-sized monochromatic painting, “In Dubious Battle,” is made up of 11 panels, measuring 7 feet high by 47 feet wide in total. She finds inspiration from art history textbooks and borrows themes from the old masters for her new compositions, giving them an old-world feel. She uses animals to illustrate lessons about the strengths and failings of human nature.

Large pieces by Rick Shaefer make it impossible to overlook the effects of human activity on nature. “Rhino” is surprisingly lifelike, especially considering it’s drawn in exact charcoal marks that manage to establish a tonal range and texture without smudging. Dark lines add to the perceived mass of the animal, and give more weight to species loss.

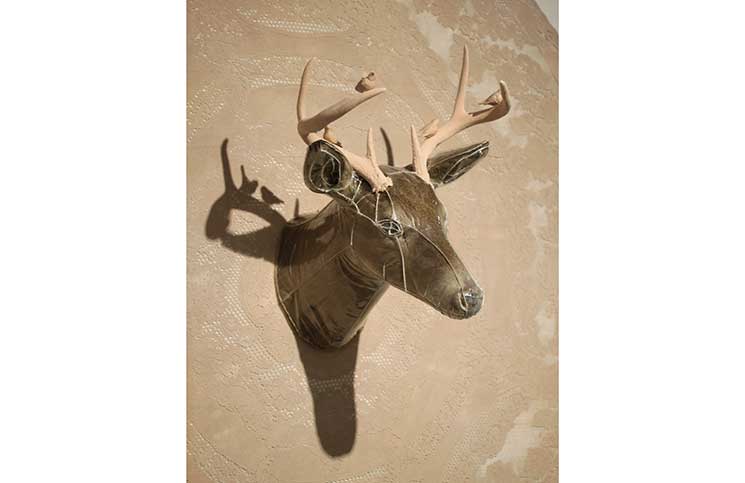

“Re.covered” by Christina Pitsch

Mixed-media artist Christina Pitsch poses questions about cultural iconography and gender identification through replicas of hunting trophies. She points out contrasts in the masculine qualities of hunting culture and the feminine gracefulness and delicacy of deer. “Re.covered” is a taxidermy deer head with porcelain antlers, covered in a hand-stitched vinyl slipcover, backed by a pink-flocked doily. The most disturbing element, the clear vinyl over the head, represents the preservation of valuables.

Randal Thurston designed a site-specific wall installation from cut-paper silhouettes of larger-than-life insects. Simply using black paper, it’s a reminder of the vast variety of living things. His work explores mortality and nature, and the shadows it leaves are intended as echoes of the world.

The Museum of Art is located at 30 Academic Way in the Paul Creative Arts Center at UNH, Durham.