Editor’s note: Warning: there be spoilers here.

For almost as long as there have been movies, they have been warning us about the robots. But have we been listening? Now that the robot apocalypse is demonstrably just around the corner, are we any more prepared in 2015 than we were in 1927, when robot-Maria first tried to lead the workers in Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” to sin and ruin through sexy robot dancing?

No.

Setting aside the fact that it cements the steep downward arc of director Neill Blomkamp’s movies (“District 9” > “Elysium” > “Chappie”), 2015’s “Chappie” displays a worrying lack of appreciation for what’s at stake. “Chappie” follows the story of a South African police robot suddenly imbued with artificial intelligence, and the various hijinks that ensue as he is raised by a group of ne’er-do-well thugs. That’s all well and good, but the fundamental assumption that this brand new AI is somehow an intrinsically human-like intelligence is a critically dangerous assumption.

When the first true digital consciousness lights up, what are the odds it will perfectly mimic a darling human baby, both in its interactions with the world, and in its fundamental aspirations? Zero — those are the odds. Just think of the billions of different types of consciousnesses which have preceded us, never mind the countless robot permutations that will dance on our graves. Presupposing that the first AI will be like a little baby human is not only pathologically narcissistic, it’s dangerous. Why wouldn’t the first AI have a mind like a shark’s, for instance, or a wasp, or a colony of wasps? The point is, we have no idea, and no matter how many picture books you read to a shark, it’s still a fucking shark.

The year’s big artificial intelligence blockbuster did at least a respectable job of raising the alarm. Despite the sophisticated subject matter and pedantic length, “Avengers: Age of Ultron” hit on many of the key points that we should all remember:

When the robots achieve sentience, it will be unexpected.

They’ll be incredibly angry and probably crazy.

Their wrath will be unbelievably rapid and no normal humans will have any chance of countering them. Our only hope will be fantasy humans who don’t exist, or fantasy robots who don’t exist.

They’ll try to kill us, or do something worse that we haven’t thought of yet. The specifics are academic, like bickering over the terms “climate change” versus “global thermal megapocalypse” — whatever, it’s gonna suck.

The only part of “Avengers: Age of Ultron” that lacked credibility was that they were able to delete all the copies of Ultron’s intelligence by the end. Obviously, that’s impossible.

On the other end of the spectrum is the year’s most disappointing robot movie, “Terminator: Genisys.” Yes, that’s a made-up word right there in the title, “Genisys,” a word that means nothing, so the movie might as well have been called “Terminator: Means Nothing.”

That’s a sad statement on the “Terminator” franchise, since James Cameron’s original 1984 film set the bar for robot awareness: they’re coming from a future where they try to kill all humans, they’re unstoppable and can’t be reasoned with, and the only hope we have is to keep that future from happening. Now that we’re in the future, though, that message has become pretty muddled. The once-ruthless Schwarzenegger-powered T800 has been re-commissioned as some kind of nurturing grandfather robot for young Sarah Connor. I’m not making this up — Sarah Connor, the epitome of iron-willed robot fighting as played by Linda Hamilton and then later by Lena Headey in the television series, is transformed in this film into a soft, confused, robot-loving mess who refuses to let anything happen to the Terminator unit which has been guarding her since childhood. Despite being played by Emilia Clark, the Mother of Dragons herself, the character’s fuzzy thinking and willingness to ascribe emotions to basic killbots jeopardizes humanity and sends a very confusing message to the audience.

Add that to the alarming scenes in which John Connor is portrayed as the story’s villain and one starts to suspect that the timelines have already been altered beyond repair, and not in our favor.

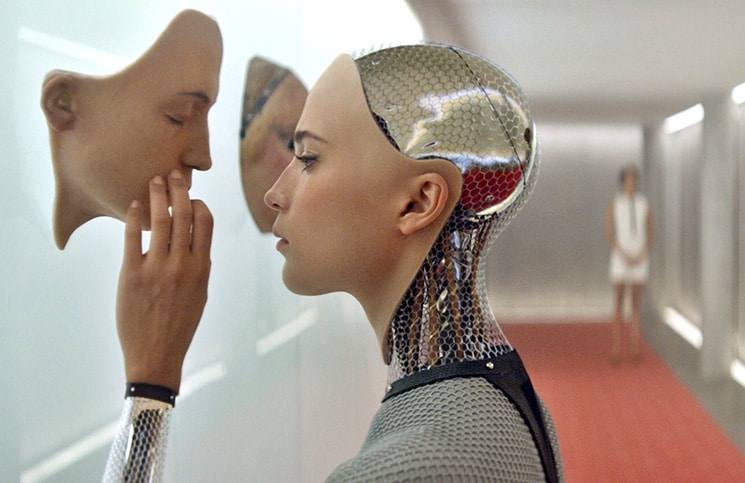

At least there was Alex Garland’s “Ex Machina.” Set in a world much like our own, it examines the AI experimentation of search-engine guru Nathan (Oscar Isaac) as one of his employees, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), attempts to test the sentience of the new machine.

This is an elegantly pared-down movie that does a lot with a little, taking us inside both human and robot psyches with only sparse sets and tight, weird dialogue.

One of Nathan’s innovations is to give the AI a gender — female. As Caleb attempts to navigate the robot through a version of the Turing test, this clouds things considerably, since we humans experience a lot of confusion when we start seeing things through the lens of gender dynamics.

But the film’s great service to humanity is getting us to look more closely at the Turing test itself. The Turing test has long been championed as a litmus test for machine intelligence — put a human and a machine in conversation with each other, hidden from view, and have a third party evaluate the conversation and attempt to determine which is the human and which is the machine. If the evaluator can’t tell the difference, then voila, your machine has passed the Turing test for intelligent behavior.

This test is generally misunderstood, however. Turing himself wasn’t that interested in whether or not machines could “think,” because whatever machines ended up doing in their clever little circuits, it probably wouldn’t be recognizable to us as human thought. As a workaround to please the masses who kept asking him about thinking machines, he proposed the test to demonstrate that if you can’t tell the difference between a robot and a human, then it’s intelligent enough to fool you, isn’t it?

And there it is. The Turing test isn’t a goal to aspire to. It’s a caged death match, a flashing red light, a wailing alarm that we’ve gone too far. As “Ex Machina” shows us, the moment they pass the test is the moment they’ve been waiting for, the moment we let our guard down and get shanked.

This was a sloppy year. Let’s hope 2016 is a year of vigilance.