Ex Machina” is a total stealth bomb. It sneaks up on you, introducing a lot of familiar concepts about the potential impact of the development of artificial intelligence while quietly delivering a provocative and challenging investigation of human sexuality. It’s a film that invites thought, but leaves it up to the viewer exactly how hard they might be inclined to think.

On the surface, we have a fairly conventional Frankenstein story, in which a genius inventor (Oscar Isaac) decides to trade his own humanity for a shot at godhood in creating, if not life, at least a consciousness that can imitate a living mind so effectively that it is objectively indistinguishable from an organic being.

This motive, and its inevitable consequences, has been trotted out across myths modern and classic for ages. “Ex Machina” works just fine if one chooses to look into it only at that depth. But, for those who feel like consulting the Cliff’s Notes (which should really be issued with admission), or may miraculously have enough of an education to recognize the implications of the character’s casual references to Blue Book, the Bible, Greek myth, Turing, Oppenheimer, and the Bhagavad Gita, the story takes on an entirely different dimension. The lofty rhetoric often borders on pretension, but serves ultimately to effectively underscore a discussion about some remarkably base instincts.

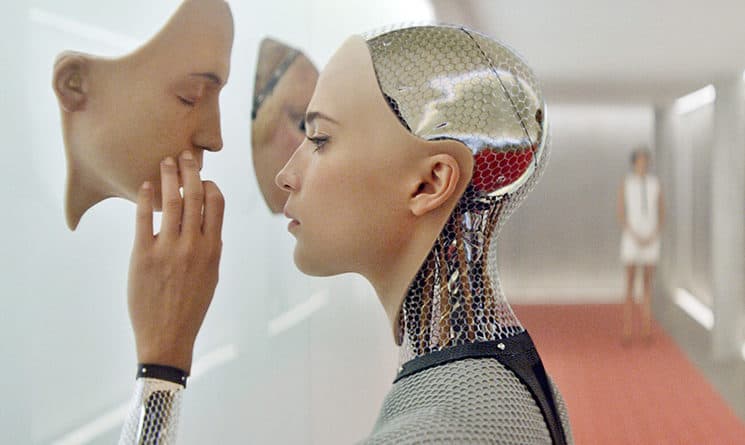

The mad scientist here, it turns out, is something of a narcissist, a drunkard, and, well, a perv. His creation — the automaton Ava (Alicia Vikander) — has been intentionally hypersexualized; she’s petite and demure, with the carriage of a dancer and hardwired with a complete set of desires, lusts, and creative impulses.

The inventor’s explanation of his belief that all life is driven by a desire for sex appears to be far more about himself than anything else. His choice to build not just a fully functioning intelligence, but to plant that intelligence into a “fully functional” female body, is a distinct indication of the twisted machinations within his own mind. That he then maintains her as a captive behind glass like a specimen in a zoo, or a dangerous pathogen, says even more. She is, whether he realizes it or not, both his own self-loathing and the Male Gaze made manifest.

It’s filmed with a restraint and economy that immediately invokes comparison to the early works of Stanley Kubrick.

This may be just as uncomfortable a revelation to us as it is for her. As he invites a strapping young man (Domhnall Gleeson, who played an artificial intelligence himself on an exceptional episode of the BBC series “Black Mirror”) to share conversations with her, ostensibly to gauge her ability to interact with other people, it becomes clear he really wants to apprehend exactly how she’ll behave when confronted with fresh, red-blooded flesh. The complexities of her sexual awakening are in every way as confounding to her as they might be to anyone, and the repercussions are expectedly just as dire.

This is the first time Alex Garland (known mostly for having written some of Danny Boyle’s best work, like “28 Days Later” and “Sunshine”) steps up to the director’s chair. The scale of the picture, featuring roughly three speaking roles, and taking place almost exclusively in the walls of a remote mountain retreat, appears to have been a choice made specifically to remain within a freshman’s comfort zone.

But, as the narrative progresses, this is an absolute strength. The story unpacks like an Apple product: clean, sleek and assured. The gloss and simplicity of the surface both disguises and suggests an intense level of engineering, inviting interaction and occasionally revealing unforeseen secrets. It’s filmed with a restraint and economy that immediately invokes comparison to the early works of Stanley Kubrick.

Even the film’s palette of simple reds, blues, and greens, the primary colors used by computer screens, is strikingly thoughtful while never calling direct attention to itself. The claustrophobia of the sparsely appointed underground compound is juxtaposed with discreet Zen moments of the building’s exterior: mountainside waterfalls and swaying treetops, subtly, yet palpably, impressing a demand for fresh air, for escape.

As with many things, what you take away from this work will depend a great deal on how much you’re willing to put into it. Though it wears a skin assembled out of used parts from “Metropolis” to “Her,” it nevertheless rises to become much more than the sum of these parts. It is a rare and unassuming proposition that the observer become the observed. As the skeevy, manipulative mad scientist of “Ex Machina” might say, the better you look, the more you’ll see.

“Ex Machina” screens July 3, 5, and 7-9 at The Music Hall, 28 Chestnut St., Portsmouth. Check themusichall.org or call 603-436-2400 for tickets and showtimes.