her journey from journalist to carpenter

It was unsexy men that drove Nina MacLaughlin away from newspapers — specifically, a list of Boston’s 100 unsexiest men she was posting on the Boston Phoenix’s website. After spending her 20s at the weekly newspaper, MacLaughlin had grown tired of life behind a desk, of the intangible products of days spent behind screens and keyboards. So she quit. It was 2008 and the economy had gone sour. With nothing to lose, and no experience to speak of, MacLaughlin responded to a Craigslist job posting (“Carpenter’s Assistant: Women strongly encouraged to apply”) and, in short order, found herself working with Mary, a self-described journeyman carpenter.

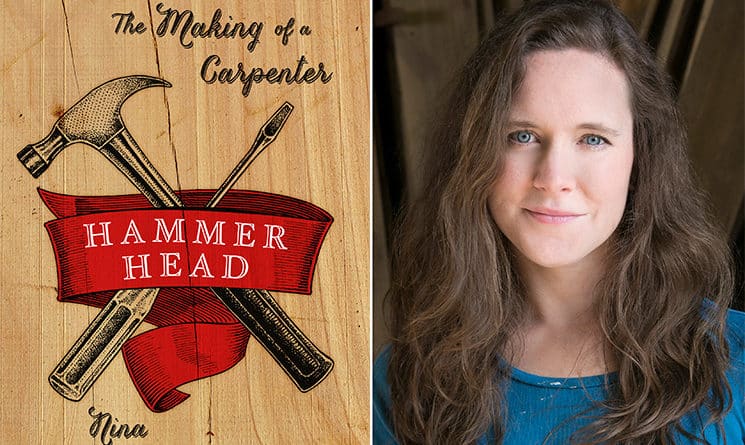

“Hammer Head: The Making of a Carpenter” chronicles MacLaughlin’s transformation. She fumbles with tools and lugs boxes of tile, screws up, succeeds, screws up again, and, ultimately, finds her confidence and ability. The book follows MacLaughlin and Mary from job to job in the neighborhoods and suburbs of Boston, as they build walls, remodel kitchens, and gut houses. There are diversions along the way — brief histories of tools, musings on varieties of wood, an examination of gender and sexuality in the context of manual labor. But the focus is square on MacLaughlin’s journey as she sheds one identity and constructs another, finding satisfaction in the rhythms of carpentry, of building something out of nothing.

MacLaughlin will read from “Hammer Head” on Thursday, April 16, at Water Street Bookstore in Exeter. The Sound recently spoke with her about carpentry, death, and finding satisfaction in work that no one may ever see.

How long did it take for you to feel confident in your abilities as a carpenter?

It’s taken a while, coming into it with no experience, because the learning curve is so steep. A year goes by, and I’ve dipped my feet into a bunch of things, and (then) it’s the process of honing your skills over and over again. There are things I feel more confident doing than others at this point, but I guess what’s compelling is there does always feel like … I still have a lot of improving to do, which is in a lot of ways similar to writing. You can always get better. After that first year and all of it being so new … it kind of evolved to this challenging, I kind of know how to do this, but I actually still suck at it … moving to years three and four and feeling pretty confident about, I don’t want to say a wide range of things, but some of the stuff, feeling like I can handle this shit on my own.

At what level do you consider yourself now? Would you call yourself a journeyman?

That might be accurate. My boss Mary, in the last six years of working together, she described herself as a journeyman. She’s a licensed contractor and although she wouldn’t say it herself, a master carpenter. The job still feels new to me. I know that with writing, I’ve written for money and professionally and for a newspaper since I was 22 or 23, but I still feel second-guess-y. I still don’t feel like I can say that. It’s the same with carpentry. Have I earned it yet? I don’t know. Both of those things, they’re funny; at what point are you allowed to say, “Yes, I am a writer,” or “I am a carpenter”? Journeyman might be possibly the level I’m at.

You write about the flashes of impatience that come with carpentry. I’m thinking of the scene in the closet, where you’re working on something difficult that no one will ever notice. Is there a tension between carpentry, which is functional and often unnoticed, and writing, which is meant to be seen and examined closely?

I think that, that closet example, there’s a certain humility that’s demanded. This little piece that literally no one … would see it, does it matter? But getting it right matters to my own sense of satisfaction and accomplishment and confidence that I’m able to get it right. And I think, in some ways, that’s translated a bit to the writing. … With the writing, even though the idea is that many eyes are reading it, I don’t think about that. I think about one or two other people giving a close look to it, and doing it, if I feel I can walk away and feel satisfied with a paragraph, and be less mindful of an audience or other people’s eyes and more that I did this work for me. That’s sort of how I’ve always approached it. It’s an interesting kind of split. We are in these private spaces of people, their homes and bathrooms and kitchens, and writing, as an act, is much more public.

It’s funny, too, that so much of what we do in carpentry (is physical). One of biggest challenges in writing is how to put into words these physical actions we do and bring it alive and make it interesting and compelling. Writing about people, that comes a little more easily, describing places and weather, but how do I describe in words this thing I don’t use words to do in any way? That was one of the hardest parts — how do I make someone know what it is to push a tile across a tile saw who’d never done that. A lot of that, too, Mary wouldn’t say, “This is how you do it, this is how you install crown molding.” … Words are the least helpful thing in the carpentry work. So it was a matter of care and focus, particularly with those sections, when I’m describing the using of tools.

There’s a recurring theme of death – decomposition, toxicity, molds, trash, etc. How’d you start seeing these undercurrents and why do you think you noticed them? What was it about carpentry that reminded you of mortality?

I have a preoccupation with it to begin with that goes beyond the carpentry work. It was very early on, in the initial things we were doing. It was almost frightening opening up these walls and seeing this wood had been rotting for years, that was wet and pulpy … this was terrifying. … It was such an immediate and stark confrontation with the impact of time. We all kind of move through time and our bodies age and we get lines around our eyes, but we don’t see time’s impact on the inside, and all of us are in this process of decay. It was sort of from the start and being aware of that from the start, being kind frightened by it, because it underlines the unceasing gush of time.

I was getting nervous about stuff we breathe in, but that wasn’t right away, partly because Mary is a little more relaxed about it; we use saws, we sand, we take down walls. But, thinking particularly about working in older houses, sometimes we’d be doing the demo work and you can’t see across the room for all the dust, and I’d think, this is not good to be taking in. I have a mind that sort of frets naturally about what cancer am I getting, what untold harm am I doing? Mary, she’s very relaxed; I read all the warning labels and she’s constantly sort of teasing me.

What’s your identity now? Are you primarily a carpenter, a writer, or something else?

Writing feels like a part of me that is at the deepest core of myself and has been since I was quite young — that’s what I wanted to be when I grew up, that’s been a part of my life, really, for almost all of it. The carpentry is obviously new, six years as compared to 36 total years, so I do feel, in a fundamental way, that writing is the deepest part of myself and the carpentry stuff still feels new in comparison. But it’s something that I know at this point, whether I’m getting paid to go into people’s homes or do it myself, I’ll be up to for the rest of my life. I feel so lucky to have both — when I’ve been working on a job for a while, I get that kind of itch to be writing, I want to be putting sentences together. And when I’m sitting there writing … I think, oh my God, get back to the deck building. It’s nice that they play on each other in such a way … they complement each other so well. I do feel like a more competent writer than a person doing carpentry, just for the sheer duration of it. And it comes a little more naturally.

You write about the excitement that comes with finishing a carpentry job, of