Theater is expert at taking an entirely uncontroversial idea, presenting it with the intensity of religious apostasy, and then convincing audiences of a position that they practically had to be tricked into disbelieving in the first place. That is, when any thought is given to the audience at all. In other cases, viewers are asked to abandon any previously held definition of the word “entertainment” and to submit themselves to an evening of brow-beating that passes itself off as instruction or advocacy and that we, like demoralized collaborators, agree to call enjoyable. Occasionally, the playwright’s facility with or joy in language compensates for his or her deficiencies in moral — or simply narrative — conviction, but one wouldn’t want to bet on this eventuality at the beginning of the evening. In short, theater has surrendered whatever connection it may once have had to our imaginations — to articulating, with fear and trembling, our dreams and our fears.

That’s why those plays that project the elemental, unsettling power of live performance, even if their ideas are muddled or inchoate, should be celebrated. “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo,” by Rajiv Joseph, produced by Veterans in Performing Arts and onstage at The Players’ Ring in Portsmouth through May 1, is such a piece of theater, a work of inexhaustible creativity and vitality performed by an ensemble that matches, in commitment and quality, any I have seen on the Seacoast. The play is funny, crude, tragic, and often profound; it is also unapologetically entertaining. You should see it — to hear language, woven with crude vernacular and restless philosophizing, that fits the exaggerated dimensions of staged stories; to witness performances of such risky vulnerability that you wonder how the actors will do it all again the next night; and to reckon with a play that, however flawed it may be, resists fashionable politics (and, unfortunately, any politics at all), covert instruction, or patronizing reassurance.

Although it takes place during the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, “Bengal Tiger” is essentially a comedy, a defiantly irreverent evocation of the metaphysical disorientation of war. The play is preoccupied not with the nature of war but with the nature of the species that wages it with such regularity and savagery. The play’s comic-ironic perspective comes from the titular main character — the ghost of a tiger who is shot and killed in the Baghdad Zoo by an American soldier — who acts as a sort of Virgil for the audience, an existential escort through the circles of this war-struck hell. An outsider three times over — he is a Bengali in Iraq, a tiger among men, and a ghost among the living — he is uniquely able to observe and comment on the cruelty of war, the absurdity of existence, and the fecklessness of God.

There are also two American soldiers, the simple and impressionable Kev and the cynical, almost mercenary Tommy, as well as an Iraqi interpreter, Musa. Each of the human characters is haunted by a ghost who has a claim to his conscience. Kev regularly encounters the peripatetic ghost of the tiger, whom he killed; Musa is tortured by the terrifying ghost of Uday Hussein (one of Saddam Hussein’s sons), for whom he gardened and who raped and killed his sister; and Tommy is hectored by the ghost of Kev, who kills himself in his despair over murdering the tiger. Ghosts, of course, are always mirrors, too; in confronting them, each character is also goaded to ask fundamental questions about himself, his past, and his beliefs.

But in emphasizing the metaphysical questions raised by the Iraq War, Joseph implicitly absolves the politicians who were materially responsible for its execution and the public, who were merely complicit. Or, rather, he writes out any suggestion of American culpability. The play’s Americans are two low-level soldiers who, though imperfect, are more venal than calculating, like a 1930s comedy duo. They have no politics or ideology; dramatically, then, they are ciphers, as much pawns of American militarism as Musa or the tiger is. But somebody is always responsible for the decision to make war, and so an American play that asks only God to account for the destruction of the Iraq War is, perhaps unwittingly, staking out a privileged and even self-exonerating political position.

Regardless of the defensibility of its argument, “Bengal Tiger in the Baghdad Zoo” at least proposes and dramatizes an argument. And Joseph’s script, with its baroque sculptures of expletives, its sardonic observations, and its prevailing tone of bemused understatement, is a particular kind of funny: bleak and barbed. Laughter catches, painfully, in the throat.

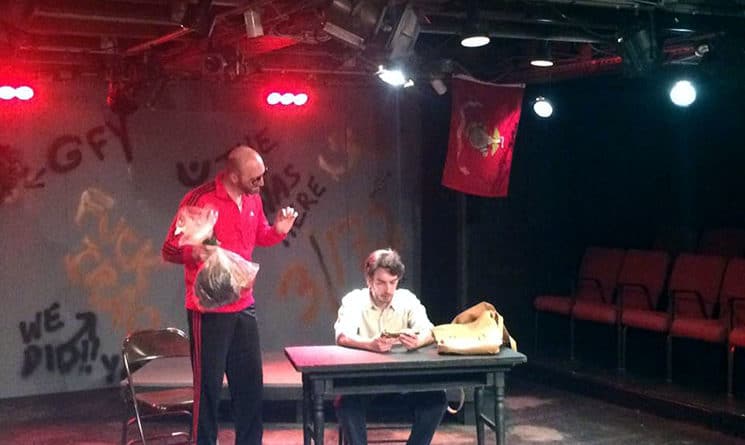

As the tiger, Billy Butler is captivating. Costumed in torn trousers and a ripped red sweatshirt, he paces the stage avidly, delivering his lines with a predatory zeal. His performance is refreshingly devoid of physical artifice — no ruffling his hair with his hand to signify thinking, no stuttering to suggest the clumsy spontaneity of speech — which means that we can focus on his reedy voice and impeccable timing, his deep familiarity with the script, and his haunted, hollowed eyes.

Scott Degan gives Kev a heart-breaking naiveté, an innocence that he feels he must conceal beneath bluster and bravado. Andrew Grassie’s Tommy is less vividly realized; Grassie’s performance feels clenched, inhibited, as though he is reluctant to embrace his character’s amorality. As Uday Hussein, Don Goettler is loose-limbed, spontaneous, and psychotic. And as Musa, Tomer Oz gives a fierce, even startling, performance; he explores the poles of Musa’s personality — his disarming guilelessness and his corrosive guilt — unflinchingly and devastatingly. In assorted smaller roles, and with few words, Nicky Mandiola manages to elicit tremendous sympathy. Indeed, we leave this show not awed by its extravagance but stunned by its moments of quietude. It is in them that we can feel ourselves trembling.

“Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” is on stage through May 1 at The Players’ Ring, 105 Marcy St., Portsmouth. Fridays and Saturdays at 8 p.m., Sunday, April 24 at 7 p.m. and Sunday, May 1 at 3 p.m. Tickets are $15, available at playersring.org or 603-436-8123.