A storm started it. In 1935, a late summer hurricane struck Key West, Fla. The morning after the storm, Ernest Hemingway took his boat, the Pilar, out to survey the damage. The carnage appalled him — men and women, floating lifeless in the water or stuck in high tree branches. But the worst was the small encampment of World War I veterans who were down in the Keys working on a New Deal project. The camp was destroyed and 458 men were dead.

“Hemingway had not seen so many dead men in one place since 1918,” writes historian Nicholas Reynolds in his new book, “Writer, Sailor, Solider, Spy: Ernest Hemingway’s Secret Adventures, 1935-1961.” “(Death) was something a soldier simply had to accept. But this was not war, and it was not acceptable.”

Raw with anger, Hemingway wrote a piece for the communist publication New Masses. The publication wanted to make use of Hemingway’s criticism of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. And while Hemingway repeatedly stressed he was not a communist, he nonetheless welcomed an outlet that would publish his story.

The piece, titled “Who Murdered the Vets?,” found an audience outside New Masses’ relatively small circulation, and eventually attracted the attention of officials in the NKVD, the Soviet Union’s secret service and a forerunner to the KGB. NKVD officials marked the celebrated writer as a potential intelligence asset. And, surprisingly, Hemingway, the quintessential American author, accepted Soviet overtures and signed up to be a spy.

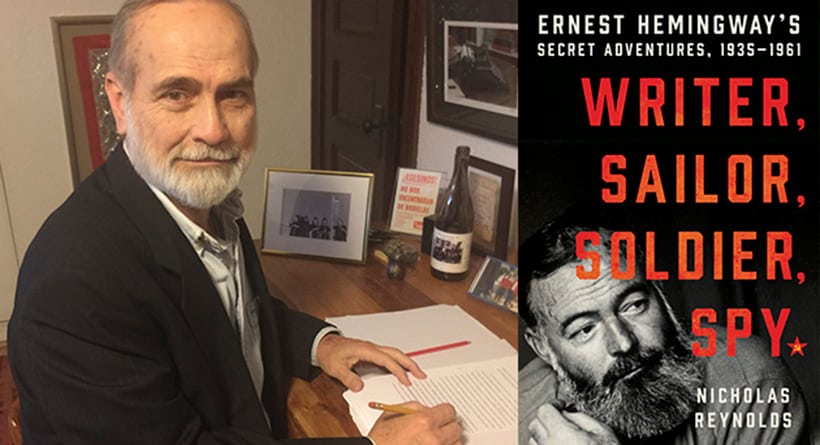

“It was almost like being punched in the stomach,” says Reynolds, a former military and CIA officer. He discovered the thread of Hemingway’s secret life in 2009 while doing research for a CIA Museum exhibit on the early days of the OSS, precursor to the CIA. A lot of digging yielded a surprising discovery: a book published in Russia in 2009 containing transcripts from Hemingway’s NKVD file.

From there, Reynolds set to work, scouring government records, archives, letters, and other sources. He uncovered Hemingway’s hidden history, a life of clandestine missions and covert meetings. Together, they told a surprising story about a writer so changed by his experience embedding as a journalist with anti-fascist fighters in the Spanish Civil War, and so angry at his own government’s weak response to the fascist movements of the 1930s, that he made a reckless, dangerous bargain.

Reynolds’ book follows Hemingway from the frontlines of the Spanish Civil War and pre-World War II China to the liberation of Paris and the tense Cold War years in Cuba. Along the way, he traces the writer’s career as an erstwhile soldier and amateur spy.

Reynolds will read from “Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy,” at The Music Hall Loft on Thursday, Aug. 10, at 7 p.m. We recently caught up with the historian for a conversation about research roadblocks, assassins with ice axes, and Hemingway’s grade as a spy.

Given your background as a military officer, CIA officer, and historian — not to mention a novelist, farmer, and mountain climber — you’re somewhat Hemingway-esque yourself. Do you have a personal connection to Hemingway’s writing?

I’ve been a Hemingway fan all my reading life. “The Old Man and the Sea” came out when I was very young, I probably read it when I was about 10 years old, and I’ve been a Hemingway fan ever since. The great thing about Hemingway’s writing is you can enjoy it at multiple levels. He likes to talk about how only the tip of the iceberg shows in his writing. I enjoy what’s above the water, and I probably enjoy the first five or 10 feet below the water, but do I go down below the bottom of the iceberg? Probably not. I’ve read almost everything he’s written; I haven’t read all the letters, nobody has, but I’ve read just about everything written and published and some things I’ve read two or three times.

I certainly immersed myself in his life and his biography over the past few years and I’ve gone in a different direction from many of my predecessors, and that’s another great thing about Hemingway. This season, there’s something like five Hemingway books out, and you’d almost think we’re writing about a different man. … There’s a richness to Hemingway’s life. There’s so much there. There’s a chronology of Hemingway’s life that came out three years ago by a gentleman named Brewster Chamberlin and you just get tired reading it (laughs). Hemingway is so active, he’s going in a hundred directions at once and he’s so good at most of what he does. He’s a superb writer, but he’s also good at fishing, hunting, sailing, boating, and he’s surprisingly good at soldiering, considering the only training he has as a solider is delivering coffee and donuts in the trenches in 1918. But it doesn’t mean I think everything he did was great.

Can you talk about the day you found evidence of Hemingway’s NKVD connection? What was your initial reaction to seeing this in print?

It was almost like being punched in the stomach. Or, it was like the John le Carre novels, where poor George Smiley is always being betrayed by his wife or by a colleague or by the opposition. So maybe I felt a little like George Smiley. … We celebrate Hemingway as honest and direct, very American even, though he lived abroad a lot. We still think of those core values as very Hemingway, and here he is sneaking off with the Soviets, and me with my background, growing up during the Cold War … the Soviets are the bad guys. It’s one thing to know a few of them and to sympathize with and like them, but it’s another to sign up with them. … It’s the subtext to what you read in the news today. There’s a line between having contact with a Russian and trading with them at arm’s length. To what degree can you shorten that distance and still be true to yourself?

Hemingway was in this murky area that I didn’t want to see him in. That led to the book. … I looked for somebody else to have done the work. I figured with all the wonderful Hemingway scholars out there, somebody had taken this on and answered the questions about what it meant for Hemingway to sign up with the NKVD. Nobody really did and they still haven’t. … I think it’s an important subject. It adds another layer to the already complicated life of Ernest Hemingway.

Can you talk about Hemingway’s political attitudes?

“Attitudes” is the right word. This is an artist, a guy who paints beautiful word pictures and tells us what people were not just thinking, but feeling. So this isn’t the chairman of the DNC saying, “We’ve got a plan and here it is.” … The core attitude in his thinking after the beginning of the Spanish Civil War is anti-fascism, and my argument is there’s a narrative arc from the age of 35 to the end of his life where he keeps fighting the same battle, and it’s the same set of values that energizes him and that doesn’t change after his side loses the Spanish Civil War. … There’s a constant anti-fascist theme and it plays out in different ways and at different times.

Can you talk about the challenges that came with researching Hemingway’s secret career? What were some notable roadblocks, and how did you overcome them?

The big roadblock is you can’t go to Moscow and see Hemingway’s original file (laughs). So we have to rely on verbatim transcripts of files by a Russian researcher who brings his notes to the West, where they’ve been dissected by the guys who spent their whole careers looking at Soviet foreign policy and espionage. … Other than that, the issue is that you’re looking for little bits to put together into a story, so I would read Hemingway’s letters and pull out different things than other people would. He was a voluminous letter writer and … in his letters, he’s having these stream of consciousness discussions … He’s pouring his heart out and there’s a great difference between him as a formal writer and an informal writer. When you read the letters, you get a sense he’s just hooking up his brain and soul to the typewriter and letting it fly, whereas when he’s writing, it’s very calculated.

So the challenge is going through an enormous amount of data to harvest a relatively small few lines that further my story. And there are different, little bits of Hemingway (material) all over the world and I probably didn’t find them all, but I found enough for this story.

photo by Becky Reynolds

The book covers some three decades in Hemingway’s immensely colorful life. With all the research, all the information, and a huge cast of characters, how, as a writer, did you balance staying true to the history with telling a compelling story?

That’s a great question, because the way historians were trained in writing is that it doesn’t really matter what the reader wants or if the reader’s happy. And there are a lot of good, maybe great history books where the historian has no sympathy for the reader and just precisely tells the story or spins their theory. My challenge … was to try and write this story in such a way that it would be fun to read and challenge me to go beyond the traditional historian thing and edge into creative nonfiction without going too far. I spent a day and a half researching what the train stations in Paris were like on a certain day in 1937, finding the schedule of the trains and the weather that day and what the train stations looked like at that time. I don’t have a Hemingway source that says, “I went to that train station and took that train.” But I do have sources that say he could have only taken this train to the docks at one o‘clock, and I do have a source that says … Hemingway asked to depart on the SS Normandy on this day, so I put these two together — he went to this train station, the weather was like this at that time, then he got on that ship. I tried to lay out the sort of the thing I’m describing in the end notes to tell people exactly what my sources are for just about everything.

How did Hemingway’s career as an amateur spy affect his writing? Did you see any of his works in a new light after your research?

This is a tricky thing for people writing about novelists. Hemingway writes novels instead of nonfiction, and he’s got his reasons for that. And so extrapolating from one to the other is kind of tricky unless you have a good bridge for it. The major work I did go back to was “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and there, after I could see what he says to other people and what he has written on the nonfiction side, you can see that (the protagonist) Robert Jordan is really pretty close to Hemingway’s own views. … The short answer is yes, but only very carefully.

Based on your own experience in the military and intelligence field, how would you rate Hemingway as a spy and as a soldier?

As a soldier I would rate him pretty highly. He’s like a really good lieutenant colonel … in his understanding of the battlefield. He’s good at small unit operations and good at going the next step up from very small units to medium-sized units. He’s got a great sense of terrain and he’s got that ability to know what’s important on a battlefield — pay attention over here, don’t worry about over there, push additional people in this direction. And he’s a pretty good flat-out soldier, pretty good at ground combat. But he’s also pretty good at a sort of paramilitary operations and military intelligence operations. I say in the book that he’s at his best in the field of intelligence when he’s outside Paris … all his skills come together there

When you look at classical espionage and that sort of political intrigue, he’s not quite as good as he thinks he is. He’s good, he understands the basic transactions. But to me, the argument that he was totally naïve … that’s not Hemingway. He knew what (the Soviets) were proposing and he knew how the game was played. The problem is, he didn’t really grasp what his role should be, especially at the time of when he signed up with them. In the spy business, that’s the transaction. The recruitment — that’s what people spend their whole careers doing, hoping to recruit an important spy, and it’s almost a kabuki dance. It’s an art form that people who are in the business understand, and he was enough in the business to understand it.

Why I’m marking him down as a spy is that he had no business saying yes to the Soviets. He should’ve left at, “I love you guys, you did great things in Spain, I’m happy to meet with you occasionally, but I don’t want a formal relationship.” Where he gets to after (signing up with the Soviets is that) he has buyer’s remorse. Do you get high marks for having buyer’s remorse? … He wasn’t as good a spy as he thought he was because that was the part he didn’t quite get. And these guys play hardball. They were actually pretty nice to him, but these are not nice people. The guys he was involved with, both of his major Soviet contacts were involved in hatching the plan to plant an ice axe in Trotsky’s brain. So after Hemingway signs up with them, he’s got to think, what’s the exit strategy? And he knows how people have left the Soviet service: death. So this is how I imagine it: As he waffles in his meetings with the Soviets in the 1940s, he’s probably thinking at the back of his mind, “Geeze, was there a cancellation clause?” And he doesn’t know, so he takes this kind of middle ground. It’s highly unlikely they’d have done anything to him, but he doesn’t know that. … He had this massive failure of judgement when he went beyond the small transactions to this larger transaction. …

Nicholas Reynolds will read from and answer questions about “Writer, Sailor, Soldier, Spy” at The Music Hall Loft in Portsmouth on Thursday, Aug. 10, at 7 p.m. Tickets are $42 and include a seat, a copy of the book, a bar beverage, and a meet-and-greet. For more information, click here.