In Kittery, Maine, among a stand of trees that feels almost like a fairy house, the children of Eyes of the World Discovery Center crow in delight at their good fortune: A tree has fallen, leaving exposed roots that overhang a pit of fresh dirt. A band of children climb up and over the tree stump and then settle into their fort beneath the roots. The school’s founder, Dawn Jenkins, sits across the clearing, a watchful eye on the kids.

“Kids are smart and, given the time and space, they often learn more out here through explorative play than we could teach them by assigning a project,” Jenkins says. “We joke about how this concept is blowing people’s minds, but it’s very simple. We are playing in the woods.”

Listen to most of the buzz surrounding early childhood education and you’d think kids today have little time for play. Kindergarten is the new first grade, preschool is the new kindergarten, and there’s no room left for joy in either, it seems. Amid the drone of standardized testing requirements, flashcards, and worksheets, however, a groundswell movement has appeared on the horizon: play-based education. These programs can feature a whirlwind of moving children, makeshift toys hacked out of sticks, improvised games, and imaginary dramas played out on top of boulders, all with scant involvement from adults.

The Seacoast is home to several play-based programs, including a handful of Montessori schools, a Waldorf school, and several “forest kindergartens.” It’s a German concept, sometimes called an outdoor nursery or nature school, that brings learning outside, where, as the Norwegian saying goes, “There’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing.”

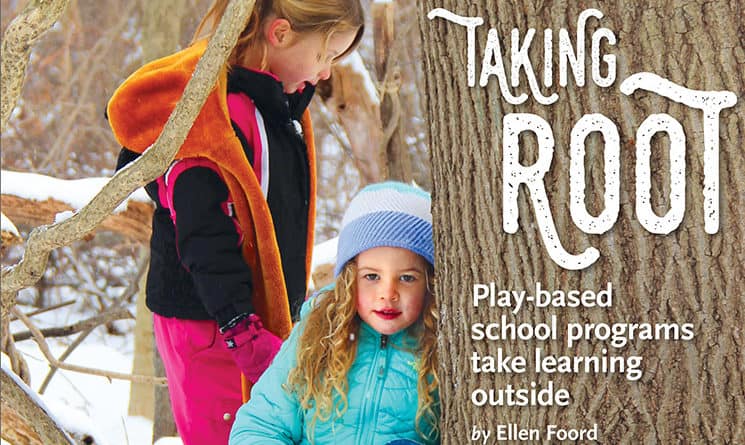

Boys at Eyes of the World Discovery Center in Kittery, Maine, make a fort out of the roots of a fallen tree. photo by Ellen Foord

From factory to forest

Why teach kids outdoors? According to Sarah Greenshields, owner of Little Tree Education, a Montessori-based preschool in Madbury, it’s a break from mainstream public education’s roots in the Industrial Revolution.

“Rows of desks, heads forward, paying attention — it replicates factory conditions,” Greenshields says. “At that point in time, producing students well-acclimated to working in factories served a purpose. It doesn’t anymore. That type of environment doesn’t foster creativity, critical thinking, social skills, resiliency, or independence. It’s an outdated model.”

Outdoor education advocates believe mainstream schools fall short in addressing achievement gaps between children. There’s also growing evidence that the disappearance of free play and reliance on forward-facing instruction might be harmful.

Author and pediatric occupational therapist Angela Hanscom is the founder of TimberNook, a nature program located in Barrington. She has witnessed firsthand the negative effects of the lack of movement in classrooms.

“I worked in an outpatient occupational therapy clinic and we started seeing a significant rise in kids who had sensory issues,” Hanscom says. “It used to be rare that kids required (occupational therapy), but suddenly, I had friends whose children needed services. Things like, ‘I don’t like wind in my face.’ How do you treat that — put a fan in a child’s face? Kids not wanting to get their hands dirty. Teachers were observing a lot of kids falling out of their chairs, leaning way over, running into each other, tripping more, hitting each other during tag with more force — not necessarily out of malice, but because their spatial awareness was way off.”

Program participants at TimberNook in Barrington spend their time climbing trees, playing in mud puddles, and building stick bridges, all while building strong social skills. photo courtesy of TimberNook

According to Hanscom, the vestibular system, which controls balance, is the key to the spike in sensory issues. Tiny hair cells in the ear send signals to the brain when the fluid of the inner ear moves. If there isn’t movement in all different directions, the fluid in the ear doesn’t move around enough and a strong vestibular system fails to develop.

Even more importantly, the vestibular system is the key to all other senses. In a pilot study performed by Hanscom at a New England elementary school, she found that only one in 12 kids had normal balance system and core strength compared to results from the 1980s.

“You need to work on the vestibular system like exercise, more than once a week. They need to play freely, and ideally outdoors, for hours each day. We’re giving kids very little or no time, maybe 15 to 20 minutes a day, and it’s not enough,” Hanscom says.

Both Jenkins and Hanscom say the soft skills children in play- or nature-based programs acquire, such as learning how to navigate social dynamics without adult intervention, put them light years ahead of their peers when they move on to a mainstream school.

“Tattling is a huge part of typical preschools, but I don’t see that here,” Jenkins says. “We set the expectation that kids will work things out amongst themselves and it’s rare that they are unable to do that under these conditions.”

At Little Tree Education, classrooms bear little resemblance to a typical kindergarten or preschool. There are no desks, no plastic toys, no flashing lights, no electronic noise — it’s wooden toys, tools, and art supplies as far as the eye can see. The children move around constantly.

At Little Tree Education in Madbury, children choose from a variety of tasks, or “jobs,” each of which teaches gross or fine motor skills. photo by Ellen Foord

The whole paradigm of who is in charge is similarly shifted in Montessori classrooms. Teachers are there, but the classroom belongs to the children, and the entire philosophy is rooted in self-led discovery and play.

“When kids participate in play-based programs like this, they have more time and space to develop certain skills and then enter first grade more fully formed,” says Greenshields, a former Dover school board member.

While there are many talented teachers in public schools, she adds, the system itself is so restrictive that the capacity of many teachers is stifled.

“A 5-year-old still needs affection and connection,” she says. “Many mainstream schools can’t allow the kind of bonding, nurturing, even cuddling that this environment offers.”

Inside and outside

For parents having difficulty reconciling the stark difference between their own free-roaming childhood and today’s much more restrictive childhood, the preservation of joyful play is a beacon of hope. But educators remind parents that it’s not an either-or proposition. According to Dan Hansche, program director at White Pine Programs