Martha Redbone wanted to follow her 2006 album “Future Street” with a project that would honor her family’s years in the mountains and coal mines of Appalachia. With roots in Clinch Mountain, Va., and Harlan County, Ky. — her grandfather was a coal miner, and she’s of mixed Choctaw, Cherokee, European, and African-American descent — Redbone thought a mix of coal-mining tunes and old mountain songs would be a fitting tribute. But then William Blake came along. Redbone’s husband and songwriting partner Aaron Whitby opened an anthology by the 18th-century romantic poet and started reading, and the two were surprised to find that Blake’s poetry made for great songs. And so they took a detour; they put the first album on hold and began work on what would become 2012’s “The Garden of Love,” in which Redbone and Whitby set Blake’s poems to music.

The album was something of a departure for Redbone, a mix of bluegrass, folk, Americana, gospel, and soul that followed up three successful R&B and soul albums. But “The Garden of Love” ended up being close to Redbone’s roots anyway, with songs that carry in them love and loss, grief and yearning, and the echoes of untouched mountains and valleys.

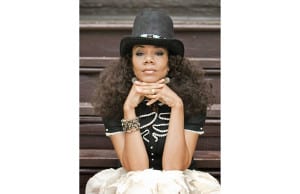

Redbone and Whitby, along with violinist Charles Burnham, tour under the name Martha Redbone Roots Project. They’re bringing “The Garden of Love” and other songs to The Music Hall Loft on June 12. The Sound recently caught up with Redbone to discuss her latest projects, working with Parliament-Funkadelic, and telling her story.

This winter, you performed the theatrical piece “Bone Hill,” about your roots in Appalachia, in New York. How do your roots inform your music?

“Bone Hill” is a piece we’re currently developing; it’s not what we’ll have for our concert on Friday. It’s a theatrical piece … that was commissioned by Joe’s Pub in New York City. We did a reading of it and the response to just those three nights was pretty overwhelming. … I’m from Harlan County, Kentucky, and was raised by my grandparents. My grandpa was a coal miner, which was the romantic story of that, but didn’t seem romantic at the time. We were a very humble coal-mining family and I grew up there and was raised by them, and then I came to New York City as a teen in sixth grade, and I’ve been in New York City ever since.

Growing up, when did you first realize you were a musician? Was there a sudden epiphany

Being from a humble family, education was the most important thing, so music was something you kind of took for granted … it’s singing in church and singing on your front porch, and nothing to be taken seriously as a career, because we weren’t a family of musicians. Usually, in the South, if you become a musician, you tend to be from a musical family … in our case, we weren’t that, so it was all about getting your education. I didn’t take up music professionally until during college. Music came and found me professionally. I started working with Parliament-Funkadelic as an artist, an illustrator, just doing some stuff working for Junie Morrison. And, from there, I developed a singing relationship there and I sang on a lot of their demos … and worked on a couple of George (Clinton’s) projects. That kind of got me … knee deep into the professional level of recording. … I was raised by these paradoxical parents who were a big part of the Civil Rights movement and did a lot of protest marching. They raised us to be whatever we wanted and to express ourselves and be fearless. I don’t think they expected us to take them up on that. I’ve only really done what I’ve loved and what inspired me and I work really hard at it, so I guess that part of it I didn’t take for granted.

Your style incorporates a wealth of genres — how did you develop it? How would you say you’ve evolved over the course of your three albums?

When I first started singing, I’ve always had the music of the mountains in my blood. It’s what I grew up with, what my mom grew up with, what my grandma grew up with, and so forth. With my partner Aaron Whitby, who’s also my husband, we’ve been songwriting partners for two decades. … We saw ourselves as songwriters first. Being from Appalachia … I have a serious respect for melody and harmony, and he’s an amazing pianist and arranger. We both believe a great song is a great song and can be produced any way, as long as that melody cuts through. … We write everything with either piano and voice or guitar and voice, and it stands up. All the bells and whistles are just frosting on the cake.

Along with being an artist, you do a lot of cultural preservation and mentorship work in Native American communities and organizations. As an artist, why do you think it’s important to give back in that way?

I don’t know if it’s important for every artist, because every artist has a different journey. For myself, I feel that it’s just something I like doing because it reminds me of being back at home with my family. I grew up getting into a lot of fights for having an Indian mom (at a time) when people thought Indians were dead. Part of my community service is to keep us alive, because many people in the world don’t think we exist anymore. … It’s one thing to hear it one time and think, “Oh, they’re ignorant and they’re not saying it to be offensive.” But, if you heard that about 500 times throughout your life, that people really think you’re dead, that you don’t even exist anymore unless you’re on a reservation … There are only four species that have to prove their pedigree — dogs, horses, the aristocracy, and Indians. We’re the only ones who have to prove how much blood we have, like a fucking horse or a dog, and that’s really messed up. … So I have to keep us alive, and we have to re-teach and re-tell our own history, because what’s been taught is a lie, so we’ve got to correct it. That’s why I do this stuff in the community and work with kids. We have to tell our own story.

What can audiences expect at the show?

Be prepared to clap and sing and have church. We usually say, “We take you to church and then back home with a nice cup of hot cocoa.” We have great fun.

The Martha Redbone Roots Project performs Friday, June 12 at 8 p.m. at The Music Hall Loft, 131 Congress St., Portsmouth. Tickets are $32, available at themusichall.org.