Al Barr’s 17-years-and-counting with the Dropkick Murphys are a little more than half of his lifelong performance career. It’s fair to say that what Barr calls his “journey” had its public debut in the basement of the Masonic Temple on Middle Street in Portsmouth in April 1985, with the first “real, show show” by the then-high school junior’s first band, D.V.A.

Rental agreements are long lost to time, and the Temple can’t confirm performance dates of a couple shows Barr organized at the venue in 1985 and 1986. But they happened, in the basement of the hall, in front of maybe 350 kids who paid $5 each to see about ten punk bands of the time.

It was an old-school era — no Facebook pages, no Twitter feeds. Advertising was by word-of-mouth, by fliers handed out in Portland, Maine or Newburyport, Mass. or around Portsmouth, with a few words during WUNH’s punk rock broadcasts.

What Barr did was round up a couple hundred bucks — $10 at a time from friends and family willing to throw him a bone and help out. That gave them enough to pay the Temple’s rental fee — to whom they might have implied a more innocent type of concert than a hardcore show featuring bands like Pledge of Resistance, Zero Mentality, or Five Balls of Power.

There was some risk. “There was always a little damage that we paid for,” $150 — a lot in 1985 money — might go to fix a broken toilet. “You hoped that a year on, the people you rented from had forgotten you were there. Have a friend call instead.”

There were handshake deals, and amazement that maybe somebody got paid — “You’re giving us $100?” Barr said one band told him. “We can get a hotel room and beer.”

And there were no contracts or legally binding agreements — the Vatican Commandoes, a decently well-known regional band (fronted by Richard Hall, later known as Moby) bailed on a scheduled appearance; the ‘noise’ band Eunuchs of Industry was kicked off the stage when they piped their “music” of static and feedback through the speakers — a threat to blow out the whole sound system one band into a 10 band show.

But it was all about that risk. In 1985, what Barr had “was the gumption to put on the show,” Barr said. And in the punk rock culture of 1985 — do it now, worry later — that was usually enough.

In 2015, between nervous renters, requirements for hired security, insurance riders, and layers of city bureaucracy, it’s not that a similar kind of concert couldn’t happen, but it wouldn’t be the same.

If that time and era had a firm ending, it could arguably be the April 5, 1994 death of Kurt Cobain, and the era – not just punk rock, but the entire music industry — is explored in the recent book The Day Alternative Music Died, by Adam Caress.

When Cobain died, Caress argued the idea of “alternative music” switched from being a true, literal alternative to mainstream music to the “alternative music” genre, like “hip-hop,” or “classic rock.” Bands like U2, Pearl Jam and others were alternative when they first hit the scene — they weren’t supposed to “fit in,” and certainly not play huge stadium shows to mainstream crowds. Barr remembered being a bit bitter when Suicidal Tendencies “sold out” in a 1986 appearance in the pop culture hit show “Miami Vice.” With Cobain’s death, alternative music became just another style to be packaged and sold.

Caress writes, “The timing of Cobain’s death and the ensuing commercial bonanza meant that…Nirvana was quickly becoming the definitive alternative template: a style, a sound and an attitude that audiences, advertisers, radio programmers, and major label shareholders could all easily recognize and understand.”

In 2015, Mumford and Sons, Modest Mouse and the Foo Fighters are identified as “alternative,” and they all play arenas and have had successful sales or top 20 hits. Foo Fighters just played two stadium shows at Fenway Park — backed by a mammoth video screen and a throne for Dave Grohl to sit, nursing a broken leg; Barr and the Dropkick Murphys served as the opening band one night.

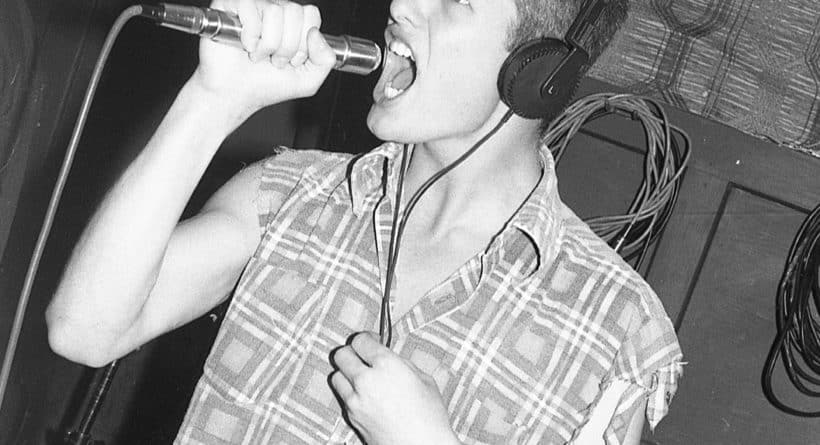

Al Barr and Karl LeBlanc practice with their band, D.V.A., in Elliot, Maine, 1984. Photo by Keith Eaton.

In 1983, The Clash had finally earned a top ten song with Rock the Casbah and hit a half-million dollar payday to play a festival sponsored by Apple Computers. They subsequently protested the $25 ticket price as too high – or maybe felt insulted and underpaid – fought with security, insulted the fans from the stage, gave a bad show for the money – and then broke up.

A band like that was an “alternative,” especially to that year’s carefully-constructed superpop of Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

It’s not that The Clash was better or worse — but it was an alternative, both in music and worldview, that doesn’t exist the same way today.

By the mid-80s, Barr had already moved past the oldies of Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones, into that more relatable teenage passion of The Clash and the Ramones.

“There was a melody there, but also a veracity,” a truth, “that my age group identified with.

“Punk rock, hardcore, was never meant to fit in. My earning a living in the genre of punk is completely unfathomable to the mindset of back then,” he said. “Punk was never meant to be popular. If you saw someone with an earring, or wearing Chuck Taylors, we were like, ‘you’re down? You’re in the club?’ There was something going on in every city, a wart on the face of rock and roll.”

Bands like Minor Threat gave voice to that teenage fight in their namesake song that Barr’s D.V.A. would often cover, a slow building rebellion against the authority that refused to take seriously the youth of the time – “Take what you can get — pay no mind to us,” they sing ironically, “We’re just a minor threat.”

Of course, to even hear that Minor Threat album took some effort – while WUNH hosted a punk show, it was still the DJ’s choice what songs would be played. Fans relied on mail-order catalogs from fanzines, or drives to small record shops in a few seacoast towns.

“But you didn’t go ‘I want this record, I want that record,’” Barr said. “They weren’t available.”

Portsmouth’s long-closed Rock Bottom Records made an effort, but the selection was “paper thin. They’d have 47 Frank Zappa albums, and I’m looking at the same Sex Pistols album that’s been there for three months.” Boston’s Newbury Comics was the true mecca, he said – but to high school kids without a car or a license, it was a rare visit.

Most of Barr’s early record and cassette tape collection came from mail order or from going to shows in Boston or Portland or anywhere, gatherings of 500 punk fans brought together by not much more than a few “smoke signals,” Barr said, of common ground and shared passions.

It’s a story retold in the Dropkick Murphys’ song Sunday Hardcore Matinee:

“Fifteen kids in a pickup truck, your Chucks, a case of beer; pack of Luckys, jeans rolled