When Andy Swanson purchased an unmanned aerial vehicle for the town of Exeter in June, he thought of it as just another tool. Swanson is Exeter’s information technology coordinator, and his plans for the apparatus — also known as a drone — were pretty simple.

“We purchased it for the town television station operations,” he says. “Our goal was to really just have some nice dramatic (aerial) footage of the town we could use in our lead-ins and lead-outs” when board and committee meetings are on the air.

According to Swanson, the town’s fire department also had plans for the drone — it could be used to take photos and video of accidents, fires, and natural disasters and help firefighters respond to a variety of situations.

But the drone never made it into the air. Residents were worried it might take photos of their property without permission, and the town’s board of selectmen ordered Swanson to keep the drone grounded until the town could come up with a comprehensive policy for its use.

“We wanted to use it to show the town in its best light,” he says. “But … there’s been some controversy. I personally don’t understand it.”

Though Exeter’s drone is grounded for now, such vehicles are flying in various locations in the Seacoast. Some are being used for work, others for recreation. As more drones take to the skies, lawmakers are looking at ways to regulate the technology, while enthusiasts hope to rehabilitate its reputation.

Bad image

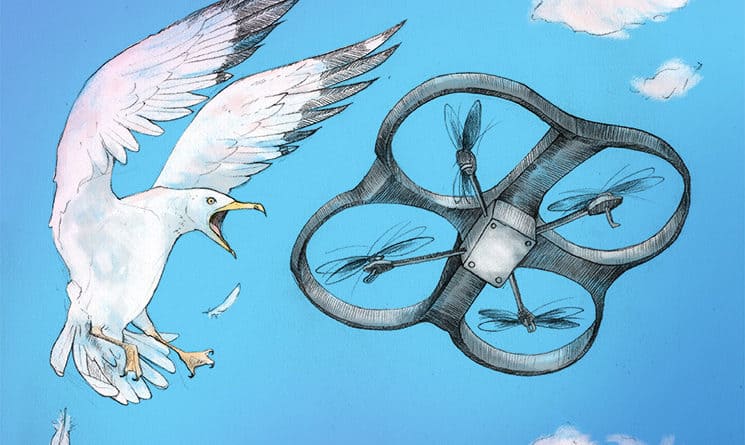

According to Swanson and other local drone users, the small, unmanned aerial vehicles have a reputation problem.

“At this point, drones are associated with military drones,” says Alex Nunn of Port City Makerspace in Portsmouth. “In reality, it’s just a flying vehicle you can control … remotely.”

The drones that Nunn and others use are nothing like the Predator drone used by the U.S. military. Armed with missiles and used for precise, targeted attacks and, sometimes, surveillance, the military’s drone program has drawn plenty of criticism. The small drones used by photographers and hobbyists are considered guilty by association. Those small drones are usually only a few pounds in weight and a few feet wide. Most are quadcopters, with four small propellers located at each corner, and a small camera mounted on the bottom.

Despite the negative image, drones are more prevalent than ever. You can order a small quadcopter with an attached camera on Amazon for about $50. Because they’re cheap and simple to operate, more people are using drones — and that’s meant more chances for mishaps. Earlier this month, a drone crashed in the stands at the U.S. Open tennis tournament in New York. Another drone crashed on the White House lawn in January. And, in July, California officials had to tell enthusiasts to keep their drones away from raging wildfires, as the vehicles made it difficult for firefighters to battle the blazes.

“There are, unfortunately, cases of people who are using these drones — that should be benign — irresponsibly … and that doesn’t do people like me any good at all,” says photographer David J. Murray, who uses drones as part of his photography business, Clear Eye Photo. “There are people definitely abusing the technology and being irresponsible, so I know where people are coming from when they are mistrustful.”

“… most people don’t think of a tank when you say ‘motor vehicle.’ But in the drone world, most people think of militarized drones.” — David J. Murray, Clear Eye Photo

New tools

Murray has been flying remote-controlled aircraft for about 10 years, and he’s been using drones in his business for four years. If you attended events in Prescott Park in Portsmouth this summer, you may have seen his drone — Murray uses the quadcopter to take photos of the crowds that turn out for Prescott Park Arts Festival concerts.

“I think (drones) are great tools for getting a different perspective,” he says. “It’s a wonderful tool when it’s used responsibly.”

Murray uses the drone for landscape, architectural, and real-estate photography, too. (He also has a van equipped with an extendible mast that goes up 75 feet.) He prefers to call it a “flying camera.” It’s a more accurate description of the drone’s function, he says, and doesn’t carry negative connotations.

“In the motor vehicle world, most people don’t think of a tank when you say ‘motor vehicle.’ But in the drone world, most people think of militarized drones. … What I have is more like a Vespa … it’s a very small, lightweight, benign, friendly kind of drone,” he says. “I try to use a word so that people understand what I’m doing has nothing to do with the military or missiles or spying.”

Andy Swanson agrees. Along with uses in Exeter’s IT and fire departments, he says the town’s land-use boards could use the drone for land walks, or gathering footage for economic development proposals.

“We are here to give information to the community,” he says. And the drone is another tool that does just that, he says.

Getting familiar

At Port City Makerspace, Nunn and about a half-dozen other drone enthusiasts are hoping a new project they’re working on will show the tools in a more positive light. Earlier this summer, Makerspace partnered with the Open Bench Project, a similar space in Portland, Maine, for Drone Chain, which aims to build and fly a drone autonomously across the country.

The first test is getting a drone to fly from Portsmouth to Portland, and Nunn says the two groups are in the early stages of planning and designing a drone that can do just that. It’s a task that sounds simple but is full of challenges, from designing the drone and figuring out the best power source to navigating the legal aspects of flying a drone over a long distance.

“Those are some pretty big challenges, and when people hear that stuff, they think of ways to tackle the problem,” he says.

Nunn hopes Drone Chain will make drones a little more familiar to the general public. He also hopes it will help clear up some of the federal laws regarding drones, which he says don’t distinguish between large unmanned aerial vehicles and small drones used for recreation or photography.

“With a lot of drone laws, they’re not quite tailored the way they need to be for people to enjoy the hobby,” he says. “Part of the project is to have a say in this discussion.”

Drone on

During the 2015 legislative session, New Hampshire lawmakers introduced two bills regulating drones. The first, HB 240, would prohibit law enforcement agencies from using drones to collect evidence. The other, HB 602, limits how law enforcement and other agencies use drones to collect evidence, establishes criminal and civil penalties for government agencies and individuals who misuse drones, and makes it illegal for drones to carry lethal or non-lethal weapons. (It’s not as far-fetched as it sounds; in August, lawmakers in North Dakota passed a law legalizing drones armed with non-lethal weapons like tear gas and rubber bullets for law enforcement.) The bills were retained in committee and could appear before lawmakers again in 2016.

According to Murray, drones are a young technology with a lot of potential. They have uses in a variety of fields, from agriculture and engineering to wildlife research and land conservation.

In the meantime, Murray does what he can to make his drone seem as friendly as possible. There’s always a pre-show announcement when he’s operating it at Prescott Park, and, if he’s flying it on hi