Satchmo at the Waldorf,” by Terry Teachout, is a well-meaning play in want of a meaning. That is, it seems to have serious and interesting goals — to humanize the frequently caricatured jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong and to understand his relationship with his manager, Joe Glaser — but it pursues these goals meanderingly, almost haphazardly, without regard for such dramatic lodestars as conflict and theme.

On stage at the Seacoast Repertory Theatre, the only thing keeping the play from wandering away from the proscenium is the largely riveting and entirely sympathetic performance of the show’s single actor, Lawrence E. Street. Street plays the 70-year-old Armstrong after one of his final performances, at the Waldorf Astoria hotel. He also plays Armstrong’s dyspeptic manager, Glaser, and, in oracular cameos, the jaded genius Miles Davis.

Street is invitingly confidential, impressively supple, and almost faultlessly fair in his characterization. His vocal evocation of these three different figures dazzles, and reminds us that the human voice weaves worlds. Even in the absence of a story worth telling, an idiosyncratic voice transmits its own truth. Armstrong himself knew as much, of course, though he doubtless preferred a good story to boot.

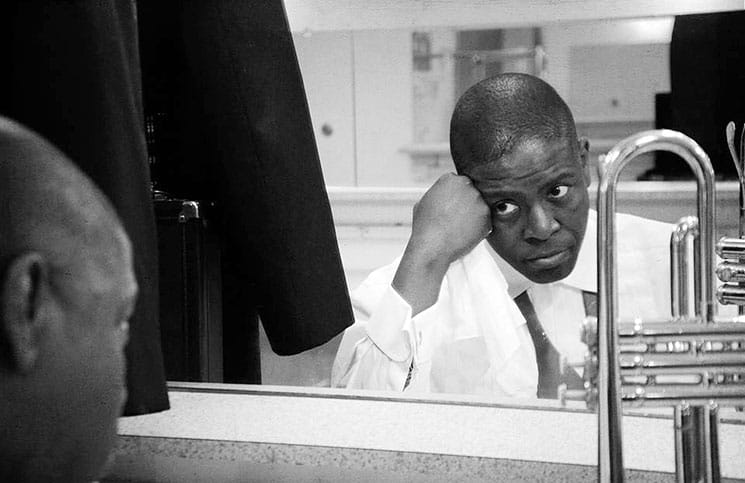

Lawrence E. Street stars as Louis Armstrong, manager Joe Glaser, and Miles Davis. photos by Kathleen Cavalaro

As the play begins, Armstrong is being applauded at the end of an evening show at the Waldorf. He shuffles into our view, his arthritic fingers hooked around his trumpet, his shoulders stooped. He does not speak for what feels like several minutes while he takes a hit from his oxygen tank and settles into his chair, center-stage. This extended silence is the most fraught moment of the show. Eventually he begins to talk, with frequent profanity and ingenuous candor, about his childhood in the Storyville neighborhood of New Orleans; his introduction to the trumpet at the Colored Waif’s Home for Boys; his loss of credibility among black audiences; his perceived inauthenticity; his artistic seriousness; his mortality; and, perhaps most poignantly, his uncertain relationship with Glaser, who has recently died.

Intermittently, the gravel-voiced, avuncular Armstrong is replaced by the shrill, fast-talking Glaser, a mob-connected event promoter who steered Armstrong’s career from 1935 to 1969. Street’s vocal transformation is startling; his Glaser is as frenetic and protean as his Armstrong is contained and self-aware. His physical transition is less vivid, less resolved, but close your eyes and Glaser is there — alive, desperate, conniving, ambitious, deeply flawed — in that voice. Glaser is part father-figure, part cynical opportunist; he admires Armstrong’s guilelessness, but he exploits it, too. Street finds, inhabits, and reveals Glaser’s ambivalent heart.

And then there are the interjections from Davis, shrouded in scarf and darkness, as judgmental as a god, his voice as wispy and ephemeral as his opinions are incontrovertible. To the saturnine Davis, Armstrong is nothing less than a traitor, a brilliant talent who has surrendered his autonomy to a white manager and his identity to white audiences. Davis finds Armstrong’s onstage persona — the big smile, the trademark handkerchief, the stories of the South — a betrayal, not a personal expression of joy in art.

Street’s sensitive and engaging portrayal of the aging Louis Armstrong … is what really sticks.

Despite the stridency of his opinions, though, it is not clear why Davis is in the play at all. To be sure, his assessment of Armstrong has contributed as much to the popular conception of him as anyone’s, but here it feels undeveloped. Davis appears three times, always chillingly, but his voice doesn’t seem so constant that it should haunt Armstrong like a shadow or a ghost, or that it should muscle its way into this brief narrative. A Davis/Armstrong show might provide rich grist for an exploration of racial stereotype in art, but in “Satchmo at the Waldorf,” this tense relationship is practically a footnote.

This diffusion is the play’s central flaw. The primary conflict of the show is between Armstrong and Glaser, but it is a conflict waged between characters who never confront each other. Such a skirmish, fought as though between two armies on separate battlefields, can only be so captivating. It certainly can never be, in any meaningful sense, dramatic. The play’s secondary conflict is between Armstrong and Davis. Although intrinsically more compelling than the other, it is sketched so hazily that we are forced to infer its terms and its import. There is the potential for the dramatizing of an unusual love triangle, but Teachout lacks the imagination or vocabulary for such allegorical geometry. His work is dully, dutifully factual. It is theater as public service.

Nevertheless, Street’s sensitive and engaging portrayal of the aging Louis Armstrong — bent but unbroken, legendary but still corporeal, essentially happy but deeply disillusioned — is what really sticks. For all of its shortcomings, Teachout’s play does do one thing well: It gives bold actors like Street a platform to show how expansive their artistry can be.

“Satchmo at the Waldorf” runs through Feb. 14 at the Seacoast Repertory Theatre, 125 Bow St., Portsmouth, 603-433-4472. Tickets are $14 to $38. Visit seacoastrep.org.